Introduction

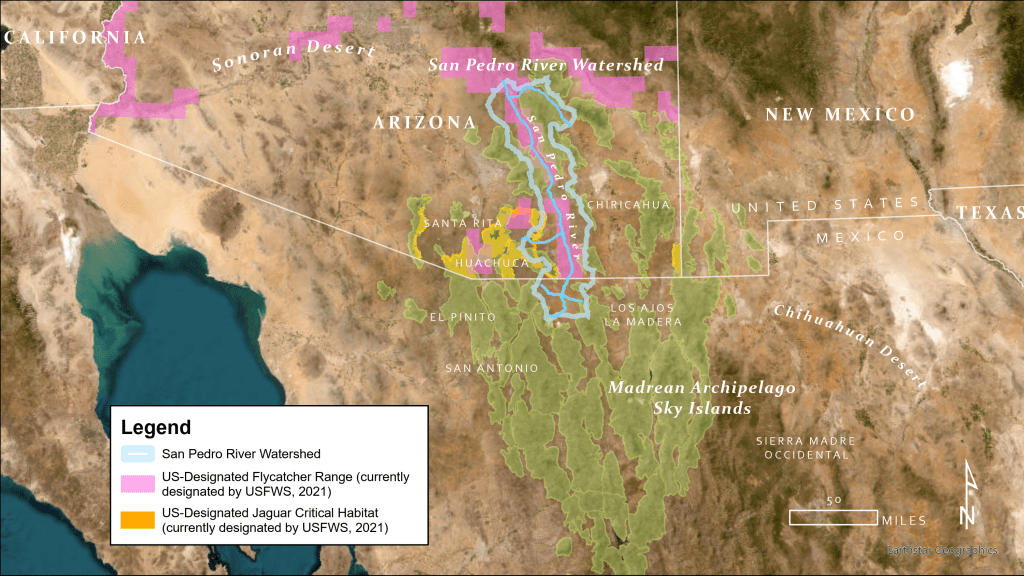

The San Pedro River drains an area of 4,720 square miles and flows north from

its headwaters in the Sierra Madre Mountains of northern Mexico for 175 miles to

Winkelman, Arizona, where it joins the Gila River (Figure 1; Arizona Geological Survey

Staff, 2009).

The river hosts a range of vegetation types from xeroriparian and saltcedar

shrublands to mesquite and cottonwood-willow forests (Stromberg et al., 2012). The

river is renowned for its riparian forests and large cottonwood-willow stands that offer

stopover habitat to migrating birds (National Audubon Society, 2022). The streamflow

permanence of the river varies by reach and has been the focus of many research and

conservation efforts in the watershed as urbanization has increased since the 20th

century. The San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area (SPRNCA) was

established by United States Congress in 1988 to give special protections to

approximately 57,000 acres of public land in the watershed and “to protect and enhance

the desert riparian ecosystem” (U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land

Management, 2022). The SPRNCA overlaps with protected habitats and critical ranges

for federally endangered species, such as the jaguar (Panthera onca) and the

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax trailii extimus) (Figure 2; U.S. Fish and

Wildlife, 2022).

In 2020, the Trump Administration waived over 30 laws, including the National

Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act, and the US-Mexico border

wall was extended in the SPRNCA across the San Pedro River and its floodplain

(Center for Biological Diversity, 2019). This border wall has fragmented habitats and

created a barrier for large mammals migrating between the United States and Mexico,

including the forementioned jaguar and numerous other species such as javelina,

mountain lion, ocelot, coyote, deer, and others. In addition to hindering wildlife

connectivity, the border wall also poses an issue for the San Pedro River in limiting its

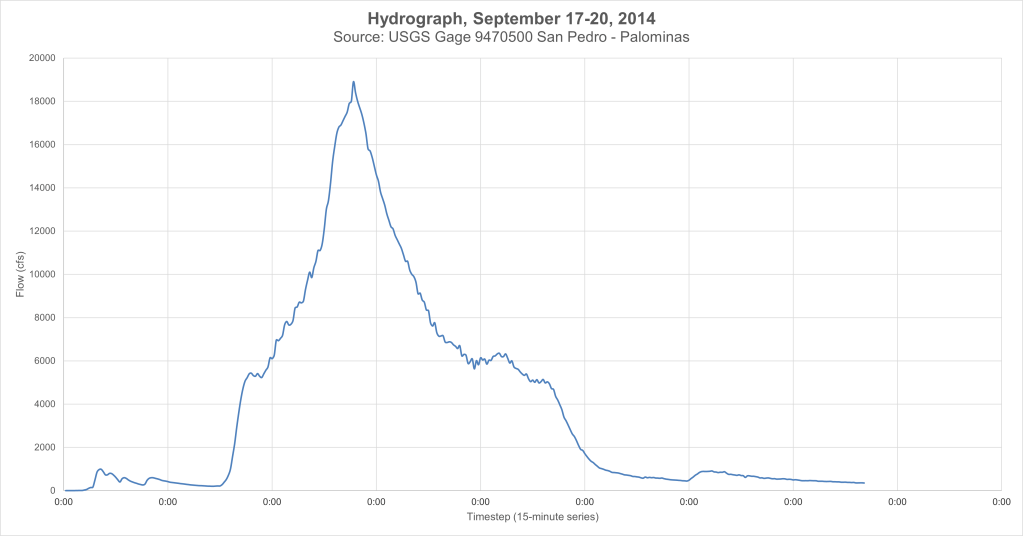

connectivity and natural debris and sediment transport regimes. While the river’s

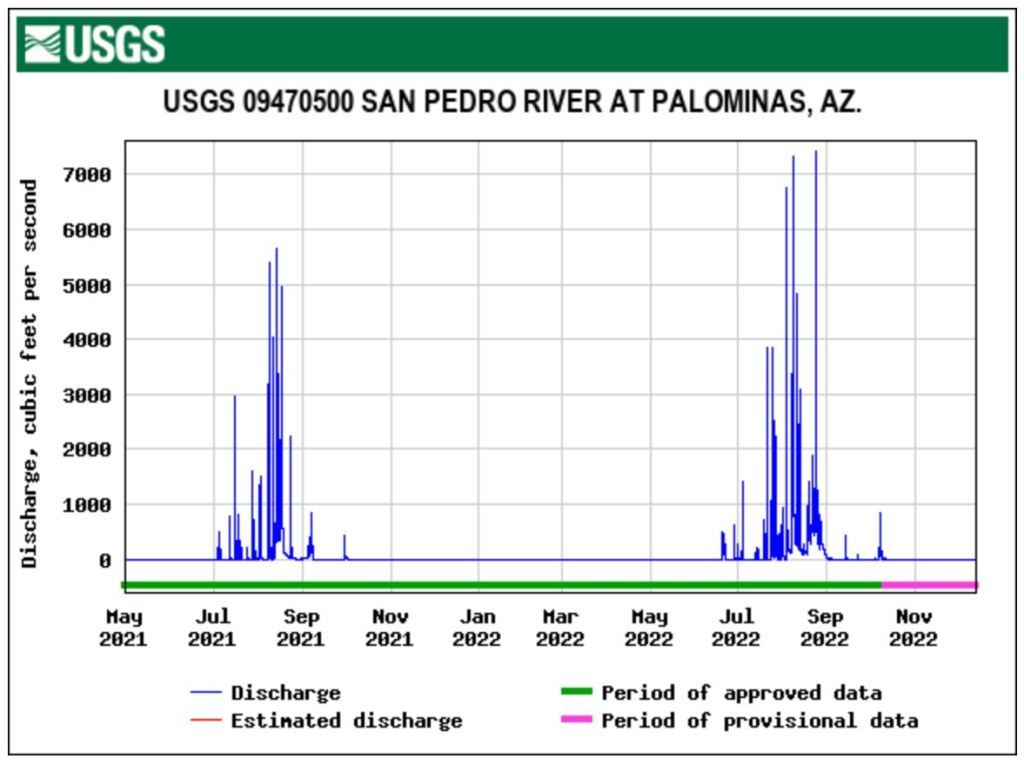

streamflow at the border is low to nonexistent for many months of the year, intense late

summer monsoon rains result in periods of rapid discharge along the river, including 15

peak flows greater than 10,000 cubic feet per second in the last 92 years on the San

Pedro River at the US-Mexico border (U. S. Geological Survey, 2022; Figure 3, Figure 4).

In this environment, such rapid floods have posed a threat to human infrastructure

developed in the floodplain, as evident from historical accounts of the river overbanking,

cutting new channels, and destroying ranches, residences, bridges, and railways. When

the border wall was constructed, a series of manually operated floodgates were

installed with the intention of allowing large floods to pass freely. However, residents

documented debris buildup at the floodgates (Figure 5) in a flood of 5,640 cubic feet per

second (a return interval of approximately 2 years) in August 2021, a year after

construction. It is not yet clear what storm magnitude and debris stage the border wall

and floodgates can withstand before failure, but the same storm system in 2021

severely damaged border wall floodgates at Silver Creek in San Bernardino National

Wildlife Refuge (Figure 6).

In May 2021, following construction of the border wall and floodgates on the San

Pedro River, but before the August 2021 storm, a group of graduate students led by

professor and fluvial geomorphologist Matt Kondolf at UC Berkeley visited the San

Pedro River. During their site visit, they measured the border wall’s floodgates,

established photo stations for repeat photography in and around the San Pedro River

downstream of the border, and measured and tagged large woody debris (LWD).

The primary questions are:

- Has there been any movement of the large woody debris (LWD) during the 19-

month period between surveys? - Is evidence of increased scouring or erosion present downstream of the border

wall on the San Pedro River following the 2021 and 2022 monsoon seasons?

Given the size of the LWD surveyed and the dimensions of the border wall’s

floodgates, it is expected that debris accumulation upstream of the wall will lead to a

damming effect. This is likely to result in increased erosion downstream of the wall as

the river’s excess energy used to transport debris and sediment will instead be

expended on erosion of the channel bed, a phenomenon referred to as “hungry water”

(Kondolf, 1997). This excess energy resulting from interference by the wall may also be

capable of transporting larger quantities and/or sizes of debris than would be expected

without the wall as a barrier. While it is apparent that the design of the border wall and

floodgates have affected the river’s longitudinal connectivity, studies quantifying the

impacts to the movement of debris, sediments, and wildlife have yet to be undertaken.

Literature Review

Geology

The geology of the San Pedro River and its floodplain is a complex stratigraphy

consisting of approximately 20 feet of Holocene alluvium (sand and gravel) followed by

50 to 100 feet of clay, silt, and fine sand terrace deposits from the late Pleistocene and

early Holocene ages, laid atop upper and lower basin fills consisting of clay, silt sand,

and gravel at 150 to 400 feet of depth deposited between the late Miocene and early

Pleistocene ages (Pool and Coe, 1999). The deposits and fills overlay bedrock of

siltstone and conglomerate known as the Pantano Formation. The surrounding

Huachuca and Mule Mountain Ranges and the Tombstone Hills consist of consolidated

rocks, including sedimentary, volcanic, and granitic (Pool and Coe, 1999). Geomorphic

contrasts and a constriction in the San Pedro River Valley structure known as “The

Narrows” separate the river into two distinct reaches: an upper reach flowing along

relatively low gradients ranging from 50 to 150 feet per mile between the Huachuca and

Mule Mountains in Southern Arizona, and a lower reach bordered more closely by the

higher-elevation Galiuro, Santa Catalina, and Rincon Mountain ranges (Wood, 1997;

Tuan, 1962). In the upper watershed, the San Pedro River’s floodplains are relatively

less developed compared to other rivers in the region, and bank stratigraphy remains

relatively intact. This makes the upper reaches of the river appropriate for studying the

formation of arroyos, or gullies carved out by strong torrents of water (Stromberg et al., 2012). Geologic relations and geomorphology of the upper reaches of the San Pedro

River are typically characterized by an entrenched main channel inset within a main

floodplain surrounded by stacked terraces and a wide inner valley, the formation of

which depend wholly on the flashy flood regime of the river.

Flood History

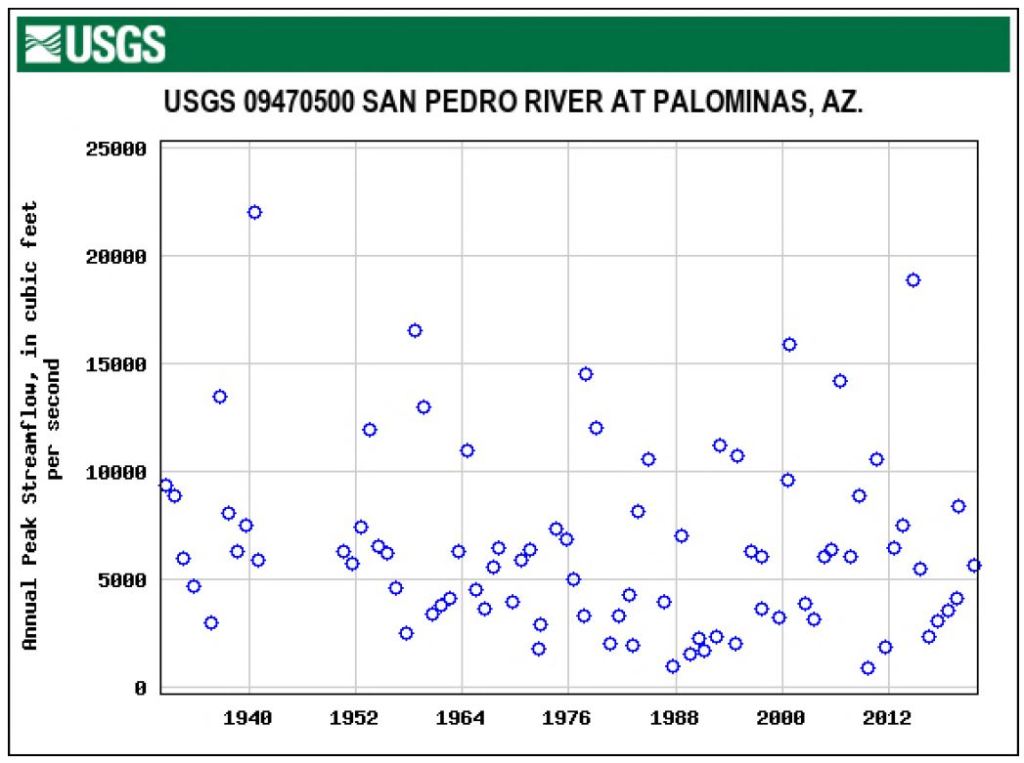

A map of cities, towns, and USGS stream gages on the San Pedro River as of

January 2023 is given in Figure 7. The gage at Palominas (USGS gage 09470500)—

established in 1926—will be the primary source of stream gage data for this study.

Between 1930 and 2022, 15 peak flows over 10,000 cfs have occurred: a return interval

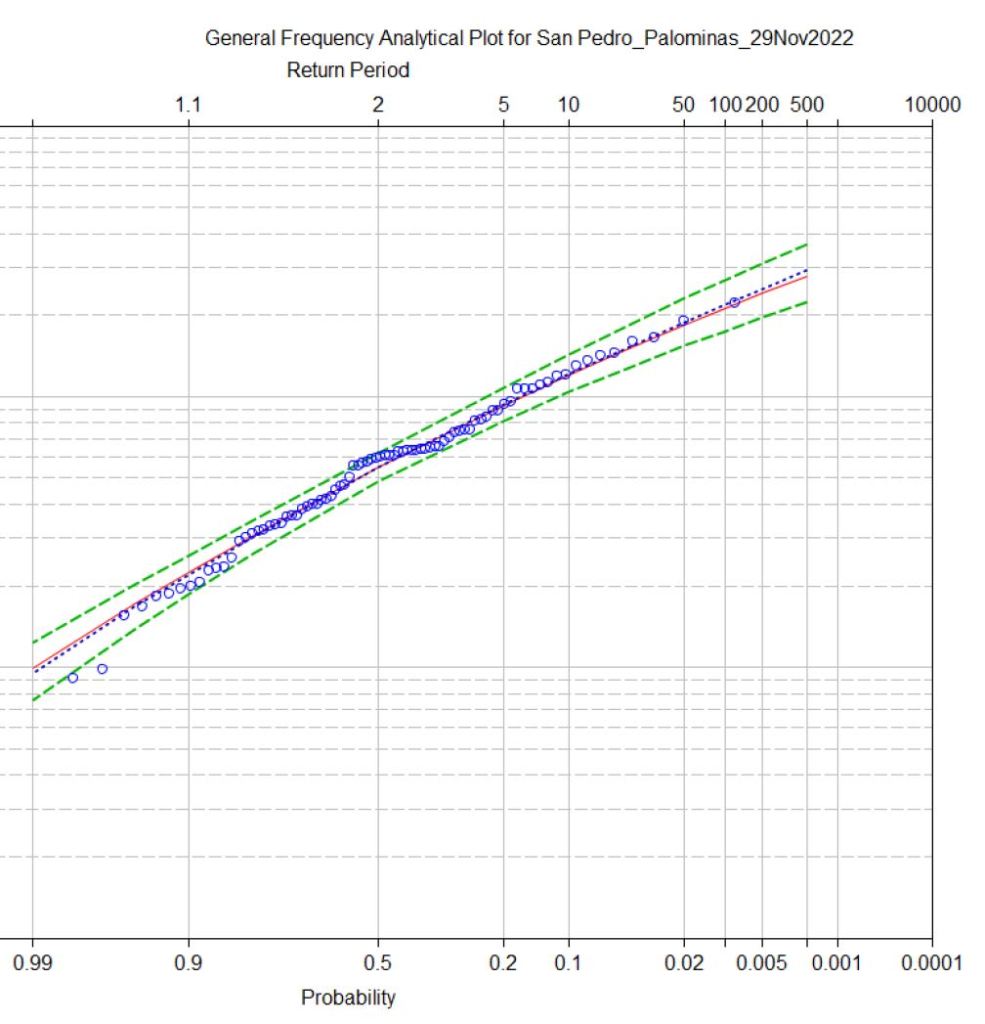

of approximately 6.13 years. From a generalized flood frequency analysis of the

Palominas gage data using HEC-SSP, a 100-year flood is estimated to be

approximately 22,000 cfs (Figure 8; U.S. Geological Survey, 2022).

Dating before modern stream gage measurements, numerous accounts from

local papers such as the Arizona Weekly Citizen, Tombstone Prospector, Arizona

Republican, Tombstone Epitaph, and others document massive floods on the San

Pedro River that began in the 1880’s. I reviewed archival evidence using public records

available through the Library of Congress (Chronicling America) and related literature –

namely that of J.C. Stromberg and G.R. Noonan – that have documented and

summarized flood events on the San Pedro River and the subsequent geomorphic

response, including channel widening, deepening, entrenchment, and arroyo formation.

Select historical accounts regarding flooding on the San Pedro River from local

newspapers are summarized in Table 1. Remarks from the varying sources range from

quantifiable measurements (e.g., “half a mile wide and twenty feet deep”) to qualitative

impacts (e.g., “several buildings destroyed”). The anecdotes range by location, but the

majority are from Benson, Fairbank, and Charleston. Other accounts are from smaller

towns of Tres Alamos, Dudleyville, Mammoth, Lewis Springs, Hereford, and St. David.

As early as 1887, local papers document large floods on the San Pedro River

that destroyed crops, agricultural fields, and buildings. In 1890, the Tombstone Epitaph

recounted that “the San Pedro River was higher than ever before known, in many

places flooding the valley several feet” (Tombstone Epitaph, 1890; Noonan, 2022;

Wood, 2015). Some accounts, such as the 1890 feature from the Arizona Silver Belt,

document geomorphic changes and arroyo cuttings due to flooding, recounting that “the

river in many places changed its channel…rapidly undermining the intervening ground”

(Arizona Silver Belt, 1890; Wood, 2015). Similarly, in 1891, the Arizona Weekly Citizen

reported a flood that “last August … dug down the channel of the San Pedro River an

average of ten feet” (Arizona Weekly Citizen, 1891). In 1914, the Tombstone Epitaph

documented a flood near Fairbank that “uprooted trees and left a layer of mud and

water over all the land” (Tombstone Epitaph, 1914; Noonan, 2022; Wood, 2015). The

same account noted that this flood on the San Pedro “was the highest it has been for

the past 20 years according to reports received from old timers in that section.”

Many of the accounts collected document damage to the Union Pacific Railroad,

which was constructed over the San Pedro River in 1880, establishing the city of

Benson. The 1896 flood, as reported by the Arizona Republican, “tore out three miles of

Southern Pacific track … sent the floodwater through the east end of town, destroying

several buildings. Twelve persons are believed to be drowned” (Arizona Republican,

1896). The Tombstone Epitaph recounted the same flood of 1896, describing that

“Benson is again all washed away … about half a mile from town east and west of the

bridge which crosses the San Pedro has been … washed away in places to a depth of

four feet … rails with ties attached lifted bodily and deposited fifteen to twenty feet to

one side” (Tombstone Epitaph, 1896; Noonan, 2022; Wood, 2015). Beyond railroad

infrastructure, damage due to flooding has been reported in other cities along the San

Pedro River valley, including Fairbank. The Bisbee Daily Review reported floodwaters in

1905 “carrying out a small bridge … likely to close the road for a couple of days. The

bridge at Clifton went out for the third time in four months … a repetition of washouts

that have kept the road closed almost continuously during the last two months” (Bisbee

Daily Review, 1905). Similarly, the Bisbee Daily Review (1914) reported that the “state

highway bridge at Fairbanks was completely under water” due to flooding on the San

Pedro in 1914. Notably, the flooding that occurred on the San Pedro in September 1926

is recognized as one of the most damaging storms in the region’s history. As reported

by the Arizona Daily Star, the floods of September 1926 were the largest floods

recorded on the San Pedro River with an approximate gage height of 23.9 feet

(Noonan, 2022; Tellman & Hadley, 2006; U.S. Geological Survey, 2022). The city of

Bisbee reported a record monthly rainfall at 10.19 inches (NOAA National Weather

Service, 2022). The USGS stream gages at Charleston, Redington, and Winkleman

recorded the peak flows on the San Pedro River during this storm as 98,000, 90,000,

and 85,000 cubic feet per second, respectively. The State Bureau of Highways reported

damage due to this storm valued at $60,000 (NOAA National Weather Service, 2022)

and the USGS valued the damages at $450,000 (U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet

2005-3081, 2022).

Additional news accounts from more recent decades further illustrate the nature

of the San Pedro River’s flashy flood regime. In early August of 2006, two men driving a

truck towing a trailer attempted to pass the Hot Springs Canyon Wash and were swept

downstream by heavy floodwaters; the men fell out of the vehicle and their bodies were

later recovered downstream (Death in Hot Springs Canyon, 2022). In August 2022, a

man and child were stranded in their car near Hereford, Arizona, due to floodwaters

during a monsoon storm on the San Pedro River (KOLD News 13, 2022).

The flood history documented in this report is limited to the portion of the

watershed within the United States and as such is not exhaustive; there are likely other

historical accounts of extreme flooding on the San Pedro River. However, the

anecdotes and streamflow data included herein illustrate the nature of the river’s flood

regime and resulting impacts to human development.

Debris Transport, Longitudinal Connectivity, and Barriers

The upper watershed beyond the border wall consists mainly of grassland,

mesquite woodland, and desert scrub in the low valley, while the headwaters near the

Sierra la Elenita-la Mariquita and Sierra Los Ajos are covered by oak woodland and

forests of pine and aspen (Kepner, 2002; Carnahan et al., 2018). As documented by

Stromberg et al. in Conservation and Ecology of the San Pedro River (2012), the floods

at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century reconfigured the river into a wide, braided

channel and “facilitated the establishment of riparian forests of cottonwood and willow”

through the processes of channel incision, widening, and arroyo development. The

cottonwoods and willows founded on the alluvial surfaces created by these large floods

now line the banks of the San Pedro River as mature stands, replacing what was

formerly marshland. Large tree branches frequently fall into the river channel during

floods, and occasionally whole trees are uprooted and transported downstream during

intense storms. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is responsible for

maintaining the border wall and floodgates on the San Pedro River. Their current

monitoring protocol is to open the floodgates at the start of the monsoon season

(around mid- to late June) and keep them open for the duration of the monsoon season,

which typically lasts until the beginning of October. The largest of the floodgates are 15

feet wide, which is not sufficient for allowing larger debris and tree falls that easily

extend beyond 20 feet in length to pass the border.

As originally defined by Taylor et al. (1993), landscape connectivity refers to “the

degree to which the landscape facilitates or impedes movement among resource

patches.” This can be applied to the border wall when considering the movement of

large mammals—such as deer, pronghorn, javelina, bobcats, and many others,

including threatened species like the jaguar and ocelot—which are too large to pass

through the narrow space between the border wall’s 30-foot-tall steel bollards. In this

way, the border wall acts as barrier to wildlife and prevents movement and migration of

large species in a biodiverse region. Robert Peters, a conservation biologist with

Defenders of Wildlife, reported that “a continuous border wall could disconnect more

than 34 percent of U.S. nonflying native terrestrial and freshwater animal species from

the 50 percent or more of their range that lies south of the border” (Peters et al., 2018;

Pearce, 2022). While much media attention has justifiably been focused on the border

wall’s impacts to wildlife movement, the wall similarly affects the movement of other

organic material. Landscape connectivity also refers to the transference of organic

resources such as large woody debris. In the case of the San Pedro River, the border

wall prevents large mammals from passing, except for in the monsoon season when

CBP opens the floodgates in anticipation of flooding, giving animals a narrow window of

opportunity to cross from one area to another (if environmental conditions even allow,

as the floodwaters may not). Similarly, and even when the floodgates are opened, large

woody debris may not be able to pass naturally if not sized small enough to fit through

the 15-foot-wide floodgates.

Building from the River Continuum Concept (Vannote et al., 1980), ecological

connectivity subsequently was described by Ward (1997) as the “exchanges of matter

(water, sediment, nutrients), energy (organic detritus), and organisms

(movement/migration) across the riverine landscape” in vertical, lateral, and longitudinal

dimensions. Longitudinal connectivity in riverine systems generally refers to sufficient

continuity in streamflow to allow resources to pass from upstream to downstream.

Currently, the dialogue surrounding barriers to longitudinal connectivity is largely

focused on dams, weirs, and culverts (e.g., Adaptive Management of Barriers in

European Rivers [the AMBER Project]; Branco et al., 2014; Rodeles et al., 2020), as

these prevent or constrict flows of water and sediments and prevent fish passage. The

border wall system is a new type of obstruction that warrants further study to better

understand and quantify impacts to streamflow, processes of erosion and scouring,

sediment, debris, and propagule transport regimes, and organismal exchange.

Methods

The methods are separated into three sections: (1) methods used during the

initial visit to the study site in May 2021, (2) methods used during a follow-up site visit in

December 2022, and (3) hydraulic modeling.

The May 2021 survey took place before monsoon season, which allowed for a

clear image of the channel’s morphology and bedform after construction of the wall, but

before any flooding. In August 2021, a flood with a return interval of approximately 2

years (Figure 15; USGS, 2022) occurred on the San Pedro River. Locals documented at

least 3 feet of debris accumulation at the floodgates following this storm (Figure 5). The

following year, in August 2022, the river reached a peak streamflow of 7,410 cfs at the

Palominas gage, which corresponds to a return interval of approximately 4 years

(USGS, 2022). The December 2022 survey was the first survey completed on the San

Pedro River following flooding after construction of the border wall.

May 2021 Site Visit

Border wall floodgate measurements, photo points, and woody debris surveys at

the San Pedro River were first recorded by G.M. Kondolf and graduate students during

an initial site visit in May 2021. Following construction of the border wall and floodgates

over the San Pedro River in 2020, the purpose of the May 2021 site visit was to

document initial conditions through (1) photo stationing and (2) tagging of LWD prior to

flooding with the border structure in place.

Establishing Photo Stations

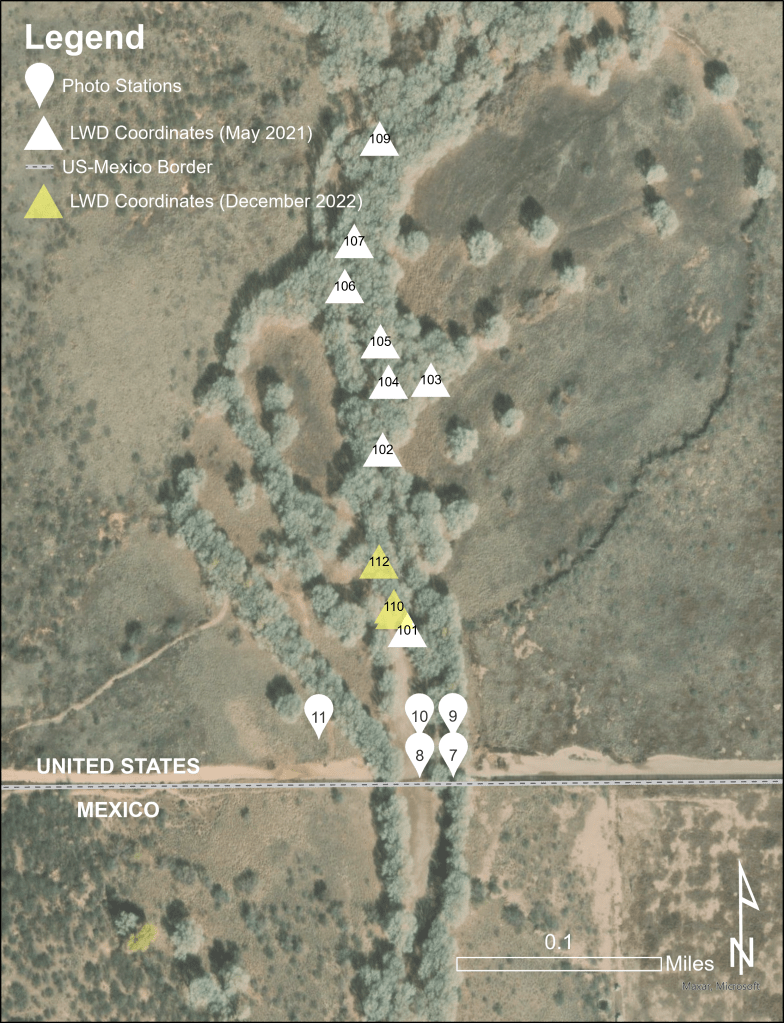

The initial survey group established five photo stations north of the border to

document conditions downstream of the border wall and floodgates, as depicted by

white triangles in Figure 9. At each photo station, the team recorded three to four photos

using a DSLR camera. Each photo was taken from a different angle to capture a

comprehensive perspective of the site conditions. The placement of the photo stations

was intended to capture the river’s bed conditions, bank conditions, location of large woody debris relative to the channel and the wall, and conditions and/or presence of

any debris accumulation on the left floodplain. Notably the photo stations are limited to

US property only (e.g., only the downstream side of the wall). The survey group used

handheld GPS devices to record the coordinates of each photo station. The

coordinates, compass bearings, and notes from May 2021 photo stationing are

recorded in Table 2.

Tagging Large Woody Debris (LWD)

Debris tagging methods are intended to document the movement of large woody

debris downstream of the border wall following floods. Tracking LWD and correlating its

movement to seasonal flooding allows us to study at what flood return interval debris is

mobilized, and if the border wall has any effect on mobilization or accumulation of

debris.

The May 2021 survey group tagged, measured, and recorded GPS coordinates

of 9 pieces of LWD downstream of the border wall using handheld GPS devices,

measuring tape, metal tree tags, and orange spray paint. Locations of LWD tagged in

May 2021 are depicted by pins in Figure 9. The survey team measured and recorded

the length, width, diameter, branch quantity measurements, and photos of each piece of

LWD to relocate the LWD during future site visits. Coordinates, measurements, tag

numbers, and notes describing the LWD surveyed in May 2021 are summarized in

Table 3.

December 2022 Site Visit

Revisiting Photo Stations

I revisited the photo stations on December, 10th, 2022 to document visible

changes since the May 2021 survey. I referenced the GPS coordinates and compass

bearings for the photo points established in May 2021 to repeat photography using a

mirrorless camera. I used a handheld GPS device and digital camera to capture photos

at each station in December 2022 (Table 2). After photographing the site from each

station, I matched each photo from December 2022 to its corresponding photo from

May 2021 to assess visible change to channel morphology. The subsequent images

from each photo station are intended to illustrate differences in bank stability, bed

conditions, and channel topography between surveys and to assess if the presence of

the border wall and floodgates led to increased erosion and scouring downstream of the

wall following flooding.

Revisiting Large Woody Debris

I used Gaia GPS and a handheld GPS device to revisit LWD that was surveyed

in May 2021 and to record new recruitment of LWD during the December 2022 site visit.

I walked to each of the coordinates recorded in May 2021 in search of the woody debris

that was tagged and referenced photos to in attempt to recognize the debris in field. If I

was unable to find or recognize the LWD at its GPS coordinates from May 2021, I

walked downstream in search of the debris and continued to reference photos to recognize the debris in field. I continued to walk 0.3 miles downstream in search of the

LWD tagged in 2021 and if I was unable to find or recognize it, I documented it as

“unrecovered.” The debris may have been transported further downstream beyond the

study reach (e.g., the 0.3 miles I traveled in search of the LWD) or may have been

broken apart during flooding and rendered unrecognizable.

Similar to the intention behind tagging the first series of LWD in May 2021, the

purpose of tagging and recording this new recruitment LWD is in attempt to recognize it

in future site visits and track its movement following the next season’s flood. I chose to

tag large debris (e.g., over 25 feet in length) that could be most easily recognized during

future site visits and was generally located in the river’s main channel at the time of the

December 2022 survey. For recording new recruitment LWD in December 2022, I used

metal tree tags and orange spray paint to tag the LWD. I used a hammer and nail to tag

each piece of LWD. I used spray paint in a distinct pattern along the length of each

piece of LWD so that if the debris is broken into smaller pieces following future floods, it

could be more easily recognized in future site visits. I used measuring tape to record the

length and diameter measurements of each piece of new recruitment LWD and used a

handheld GPS device to record the coordinates where each piece of LWD was located.

I took photos and descriptive notes for each piece of newly recruited LWD that was

tagged. It should be noted that this debris may have been present during the May 2021

site visit, but may have not been tagged at the time.

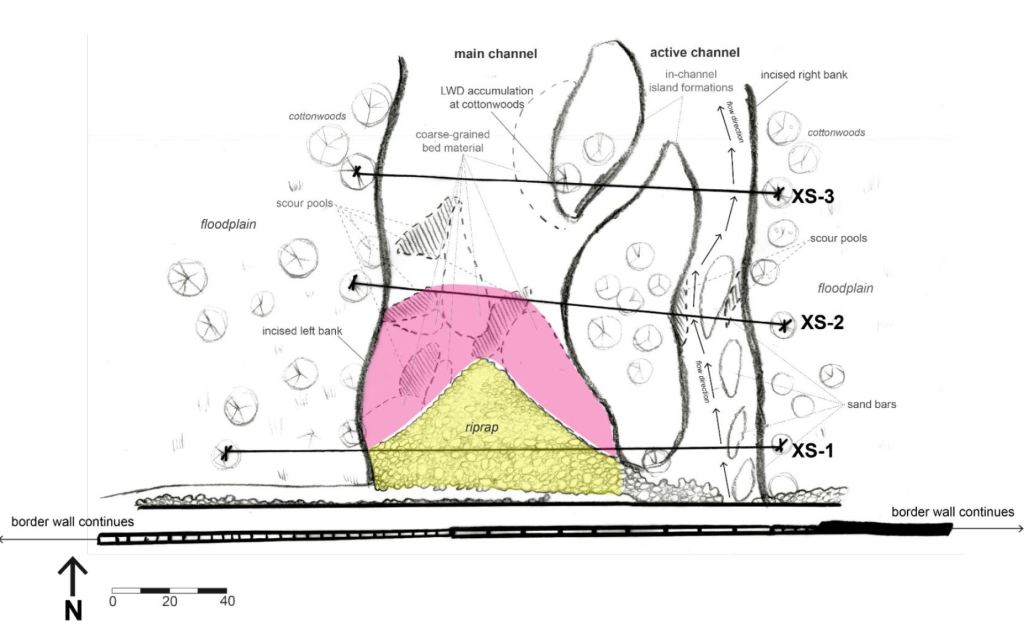

To examine changes in channel morphology over time, I established benchmarks

for three cross sections downstream of the border wall in December 2022. I located

benchmarks for each cross section on an existing mature cottonwood on either bank of

the river. I tagged, spray painted, photographed, and recorded the GPS coordinates of

each cottonwood used as a benchmark for use in future surveys. I located each cross

section with the intention to capture the topography of the river’s banks and channel at

three different locations:

Cross-Sectional Surveys

- A location closest to the wall and where the riprap pile and scour pools were

most prominent. - A location further downstream where the riprap had settled and the channel

took on a more homogeneous and less topographically dramatic form. - A location further downstream where a 5-foot pile of debris had accumulated,

and a scour pool had formed near the in-channel island between the wider,

historic channel and new, narrower, active channel.

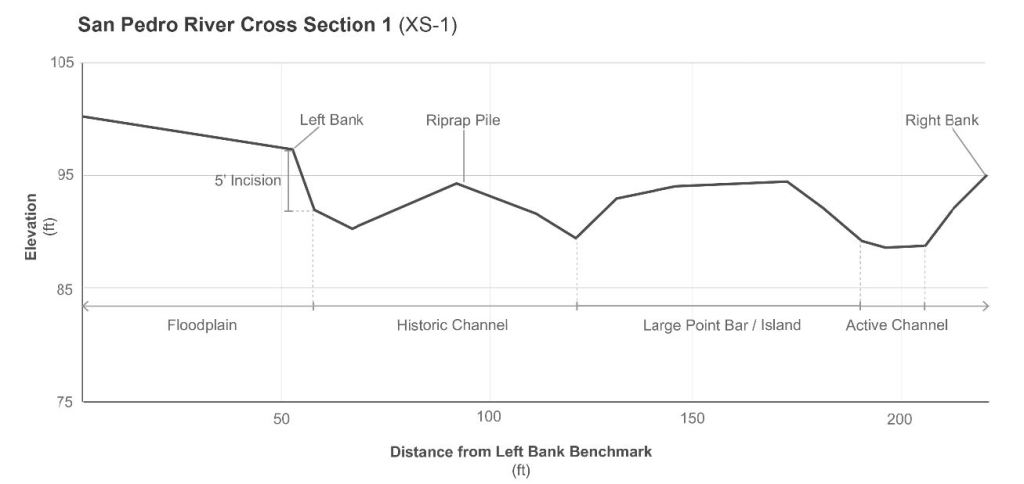

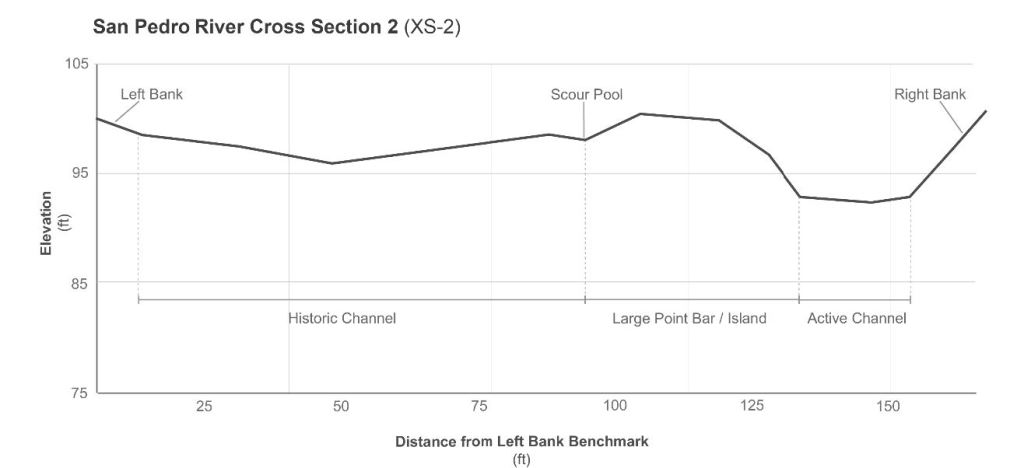

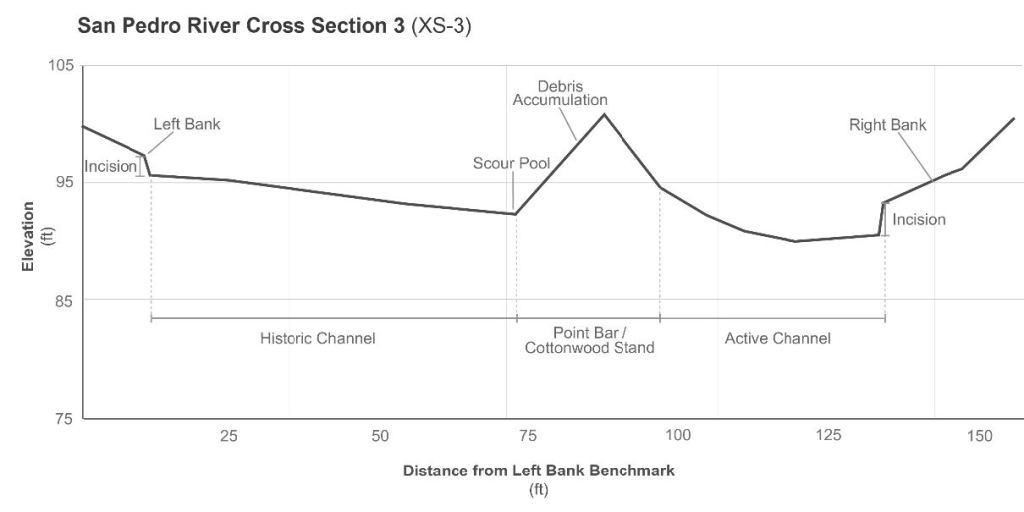

I recorded cross sections beginning nearest the border wall (Cross Section 1;

XS-1), where bank incision, scour pools, and a large pile of riprap were observed. Cross

section 2 (XS-2) was surveyed further north from the wall, beyond where the riprap had

been transported. Cross section 3 (XS-3) was the furthest cross section from the border surveyed and was intended to capture a large pile of woody debris accumulation between the smaller active channel and the wider historic channel. I used a level, stadia rod, and measuring tape to conduct the cross-section surveys, following procedures described in Harrelson et al. (1994). For each cross section, we recorded foreshots at approximately 20-foot intervals and at slope breaks and other key points along the cross-section (e.g., the top of the riprap pile, the water line in the active channel, the channel thalweg, etc.). The intention of establishing these cross sections was to assess the topography of the channel as of December 2022 for comparison in future surveys to detect changes in channel form following seasonal flooding.

Grain Size Analysis

I used the Wolman Pebble Count method (1954) to measure the river’s natural

bed material and the riprap placed downstream of the wall following construction. Using

the pebble count method, I collected and recorded the intermediate (b) axis

measurements for 100 pebbles of each type (e.g., I collected 100 particles classified as

riprap and 100 particles classified as “natural” bed material). Locations where material

was collected for pebble counts are depicted in Figure 13. I chose clearly defined

locations of (1) small riverbed gravels and (2) riprap for the pebble counts.

Hydraulic Modeling

I modeled the border wall using the USACE’s Hydrologic Engineering Center’s

River Analysis System (HEC-RAS) and the floodgate dimensions and quantities

recorded by the May 2021 survey team. The border wall system at the San Pedro River

consists of 9 main channel gates that measure 15 feet in width and 20 feet in height, as

depicted in Figure 14. Adjacent to the main channel gates on each bank of the river are

smaller gates that measure 5.5 feet in width and 12 feet in height. 4 of these smaller

gates are constructed on the right bank, while 52 are installed on the wider, shallower

left bank, where the channel was located before migrating to its current position.

I used a 1-meter resolution digital elevation model from the USGS (2021) to build

the terrain and modeled the wall as a 10-foot-wide, 30-foot-tall weir with a weir

coefficient of 2.6. I modeled the floodgates according to their opening sizes measured in

the field. The rate of opening and closing was set constant at 12 feet per minute with a

minimum water depth of 2 feet required for the gates to open and close, respectively. I

selected a roughness coefficient of 0.05 based on field observations from the May 2021

site visit and comparison to roughness estimates of other rivers on a visual basis based

on the Roughness Characteristics of Natural Channels (Barnes, 1967; Appendix A). For

the upstream boundary condition, I used hydrographs from the USGS gage 09470500

(San Pedro at Palominas) for a stage time series to simulate a 2-year storm (Figure 15)

and a 50-year storm (Figure 16). For each storm simulation, I modeled four scenarios of

debris accumulation:

- No border wall (natural condition).

- Wall and floodgates present with 0 feet of debris accumulation (gates clear).

- Wall and floodgates present with 3 feet of debris accumulation.

- Wall and floodgates present with 6 feet of debris accumulation.

For each simulation, the downstream boundary condition was held constant at

normal depth. I held the existing grade slope for distributing flow at the upstream and

downstream boundaries as constant at 0.01 and 0.03, respectively, based on the

average slope at the upstream and downstream boundaries of the study site (NASA

SRTM DEM, 2022).

To model the varying debris accumulation conditions, I assumed that only the

main channel gates would be affected (e.g., low flow gates on left and right banks

remain clear of debris in all simulations). For each stage of debris accumulation, I

reduced the main channel floodgate opening size and increased the main channel

floodgate invert elevation by the same dimension to simulate a damming or weir effect

(e.g., to simulate 3 feet of debris accumulation, I reduced opening sizes from 20 feet to

17 feet and raised the invert elevation from 1302 feet to 1305 feet; to simulate 6 feet of

debris accumulation, I reduced opening sizes from 20 feet to 14 feet and raised the

invert elevation from 1302 to 1308). The conditions and assumptions for hydraulic

modeling are summarized in Table 4. I compared the resulting maximum inundation depth and maximum flow velocity maps from each event and debris accumulation simulation to assess at which storm magnitude and stage of debris accumulation that increased flooding, scouring, or

erosion may occur.

Results

Surveys were completed on Saturday, December 10, 2022, and Sunday,

December 11, 2022. On Saturday, December 10th, the weather was clear, sunny, and

the average temperature was 57.2 degrees Fahrenheit. Wind speeds hovered between

5 and 7 miles per hour headed South/Southeast. On Sunday, December 11th, the

weather again was clear and sunny, with an average temperature of 60.4 degrees

Fahrenheit. The wind speeds picked up later in the day and reached up to 15 miles per

hour in the South/Southwest direction.

On both Saturday, December 10th, and Sunday, December 11th, there was active

streamflow in the narrower, separate channel near the right bank (e.g., east) of the San

Pedro River. No streamflow was present in the wider main channel at the time of the

December 2022 survey. The streamflow in the narrower active channel was measured

to be approximately 3 inches in depth from the thalweg where cross sections were

surveyed. USGS records from the Palominas gage (2022) indicate the streamflow

hovered around 1.5 cfs on both survey days.

Photo Stations

Results of May 2021 and December 2022 photo stationing are reported in Figure 17. The left column corresponds to photos taken during the May 2021 site visit and the

right column corresponds to photos taken at the same GPS location and compass

bearing during the December 2022 site visit. Photographs of the river in May 2021

represent the state of the river following construction of the border wall and before the

first monsoon season. In comparison, photographs of the river in December 2022

represent the state of the river two monsoon seasons following construction of the

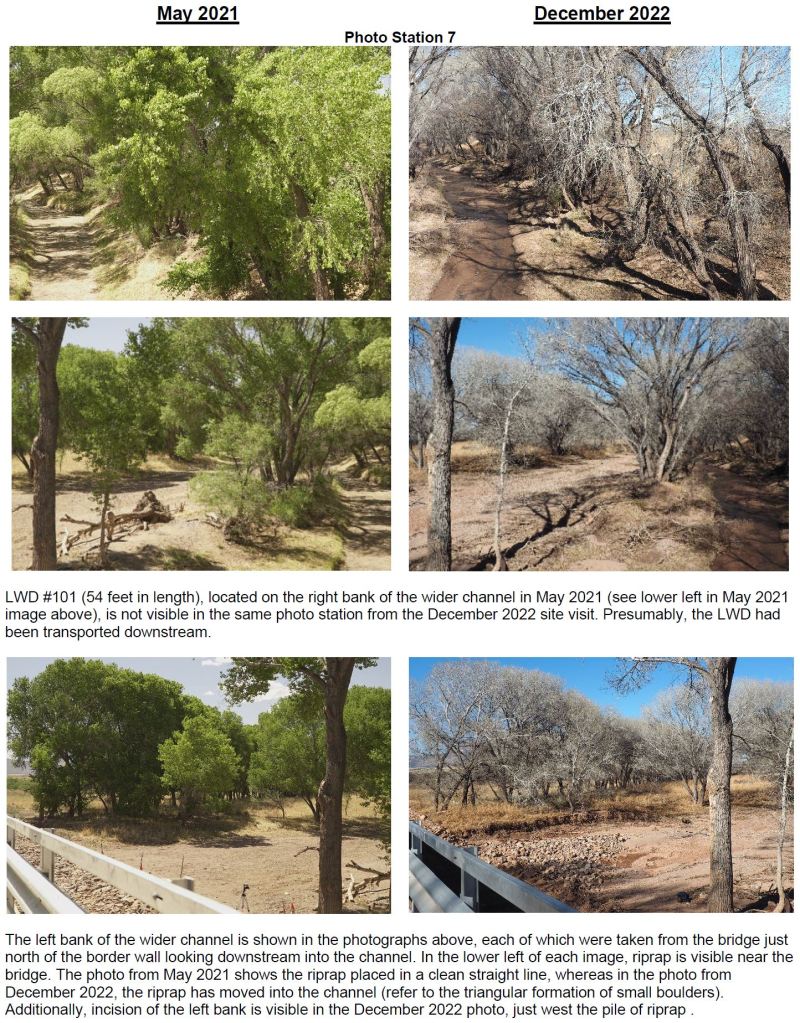

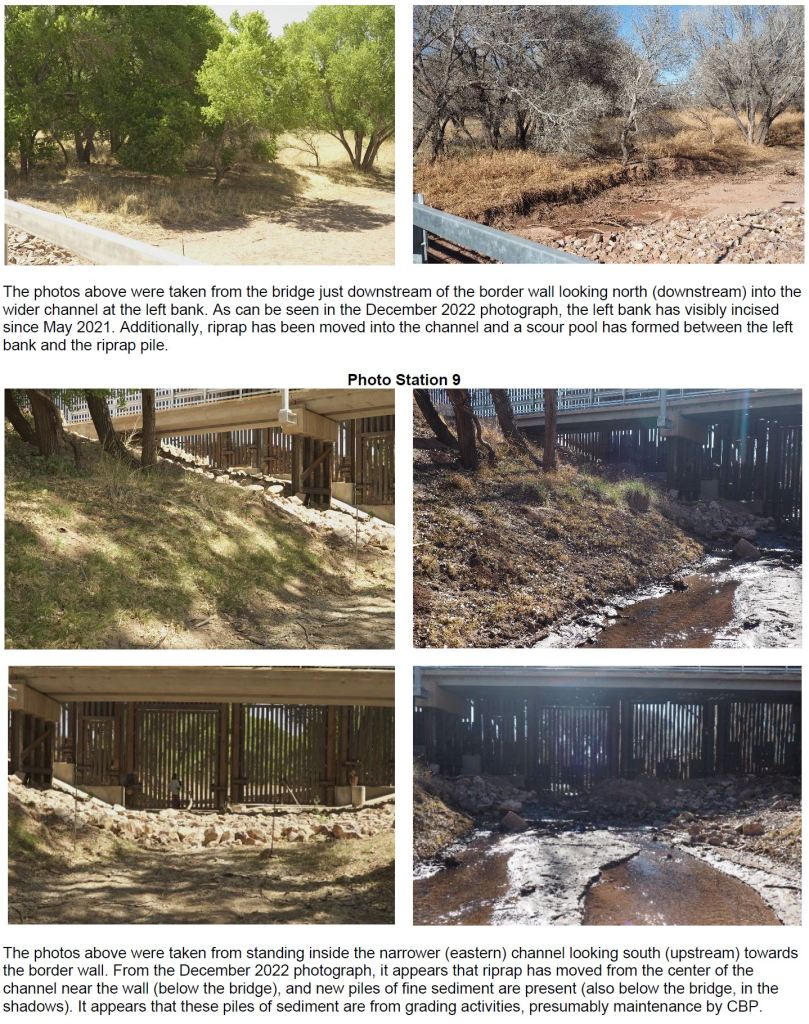

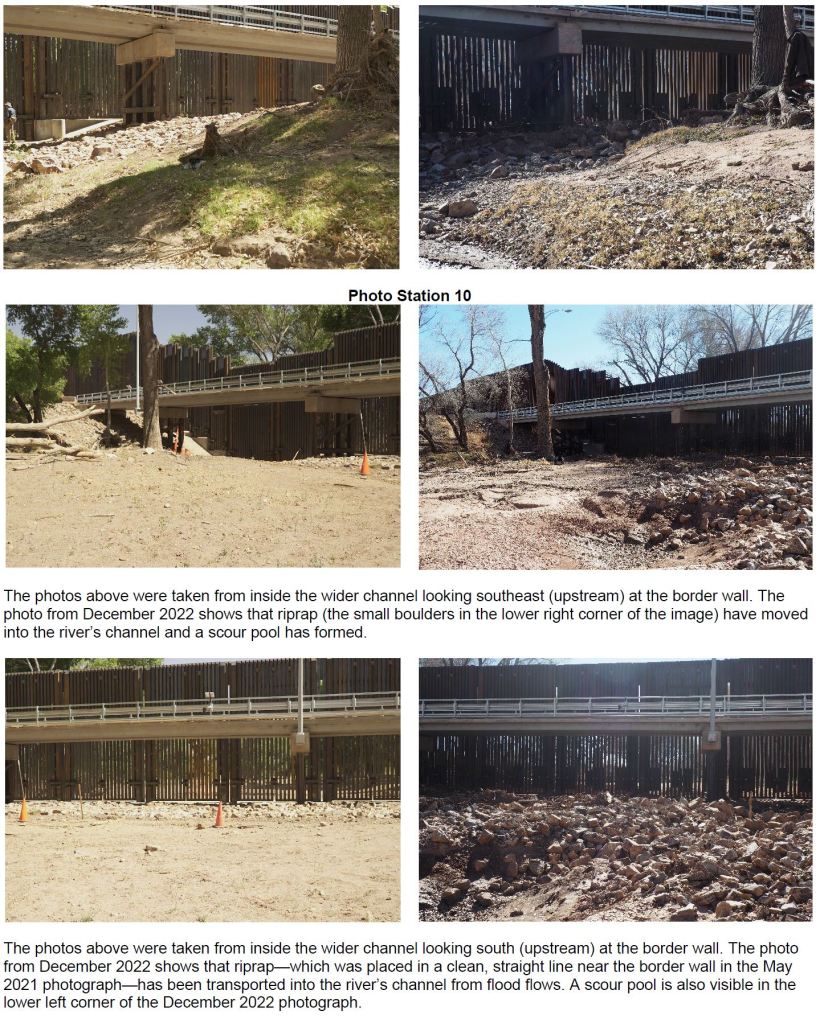

border wall and floodgates over the river and its floodplain. The repeat photos from station 7 indicate that LWD #110 was moved downstream between May 2021 and December 2022. Comparison between subsequent photos also indicate a change in bedform from a flat, sandy channel in May 2021 to a topographically complex channel made up of gravels and small cobbles in December 2022 (Figure 17). This is most clearly evident in the third photo from station 8. Photos from stations 8 and 10 show that riprap which was placed in a clean, straight line following construction of the floodgates was transported as far as 54 feet downstream by December 2022. The third photo from station 7 and the fourth photo from station 8 are perspectives into the wider channel taken from the bridge near the border wall. Incision of the left bank between May 2021 and December 2022 is evident from these images.

Similarly, the fourth photo from station 10 offers a perspective from within the wider channel where the incision of the left bank is clearer. Scour pools and piles of riprap are

visible adjacent to the incised channel in this photo.

The second photo from station 9 is a perspective from within the narrower active

channel facing south in the direction of Mexico. Where riprap was placed in this channel

in May 2021, from the December 2022 photograph, it appears that much of this riprap

has either been transported downstream with floodwaters or intentionally removed. The

first photo at station 10 is a perspective from inside the main, wider channel facing

south/southwest in the direction of Mexico. This photo captures a large scour pool that

had formed adjacent to the riprap between 2021 and 2022. Similarly, the second and

third photos at station 10 illustrate a large pile of riprap-originally placed neatly

downstream of the wall at the time of the May 2021 survey- transported into the channel

in December 2022. A scour pool is also visible on the left side of the riprap pile in the

2022 images. The fourth photo from station 10 is a perspective from the same location

inside the main, wider channel, facing south/southeast toward the left bank. The riprap

pile is again visible, as is the incised left bank and a scour pool directly adjacent.

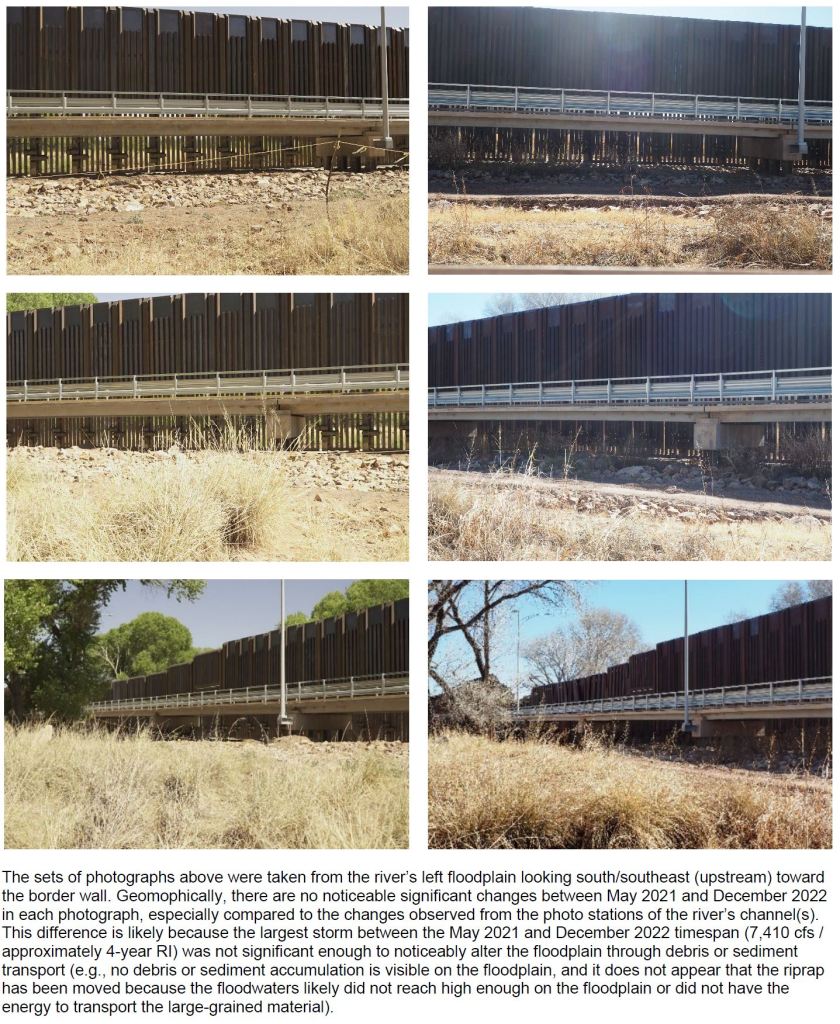

Repeat photographs from station 11 on the river’s left floodplain do not indicate

notable or remarkable changes between May 2021 and December 2022 surveys.

Debris Surveys

Each of the 9 pieces of LWD tagged in May 2021 were located downstream of

the border wall and were situated within one of the river’s channels (either the narrower

channel to the east, or the wider channel to the west). Two pieces of LWD were located

within the wider channel (101, 102) Four pieces of LWD were located on the right bank

of the narrower channel (103, 104, 105, 107). Further downstream from the wall, the

two channels combine into one larger channel. LWD #106, 107, and 109 were tagged in

this reach. LWD #103 was located the furthest up on the floodplain of all the LWD

tagged, and was situate on the right (eastern) bank of the river.

Of the debris tagged in May 2021, the average length was 27 feet and the

average width was 5 feet. The largest piece of LWD tagged in May 2021 (LWD #101)

and measured 54 feet in length and 6 feet in width and was located closest to the

border wall (e.g., furthest south) relative to the other LWD tagged. At 14 feet in length

and 1 foot in width, LWD 104 was the smallest piece tagged in 2021. Each of the LWD

tagged in May 2021 appeared to be cottonwoods. Except for LWD #105, all pieces of

LWD that were tagged still had a majority of their bark. LWD #105 appeared to have

been older, as it was stripped of its bark and smoother than the other pieces of LWD.

Results from May 2021 and December 2022 debris mapping, including GPS

coordinates, photographs, length and width measurements of debris, and descriptions

of location relative to the channel are summarized in Table 5. Figure 10 depicts the

LWD that was tagged in May 2021 and recovered in December 2022 (marked as a

white triangle) and the GPS locations for new recruitment LWD that was tagged in

December 2022 (marked as orange triangles).

Of the nine pieces of LWD surveyed in May 2021, only one was found in its initial

position during the December 2022 site visit (LWD 105; Table 5; Figure 10). LWD

measured 18.5 feet in length and 3 feet in width and was located on the right edge/bank

of the main channel in May 2021, where it remained when we recovered it in December 2022. The remaining LWD were not recovered during the December 2022 site visit.

LWD tagged in 2021 that were not recovered in 2022 may have been transported

downstream beyond the 0.3-mile study reach I traveled in search of the LWD. LWD may

also have been broken apart during floods, rendering them unrecognizable during the

December 2022 site visit. We tagged 3 new pieces of LWD in December 2022 that were not tagged in May 2021 (Figure 11). The locations of new recruitment LWD tagged in December 2022 are shown in Figure 10. GPS coordinates and descriptions of the new recruitment debris

tagged in December 2022 are recorded in Table 5. The new recruitment debris tagged

measured between 26 and 43.5 feet in length and were generally located near within

the river’s main channel downstream of the border wall.

Channel Surveys

Figure 12 indicates the location of each cross-sectional survey. Cross sectional

survey results from the December 2022 site visit are recorded in Figure 18.

Cross section 1 (XS-1; Figure 18) is the furthest upstream (south) cross section

before reaching the border wall. The benchmarks established for this cross section are

cottonwood trees on the left and right banks of the river, each marked with a nail and

orange spray paint. Cross section 1 captures where the left bank has incised by

approximately 5 feet (station 55) and where a scour pool has formed in the channel

adjacent to the left bank (station 58). The average slope from the top to the base of the

left bank was measured to be approximately -72 degrees. The scour pool nearest the

left bank was measured to be 1.8 feet deep and 16 feet in width (measured from the

base of the left bank [station 58] to the edge of the riprap bordering the western wide of

the scour pool [station 74]). Bordering this scour pool near the east bank was a large

pile of riprap, which was transported into the channel from where it was originally placed

near the bridge downstream of the border wall following its construction in 2020. At

cross section 1, the riprap pile extended for 39 feet (e.g., eastern edge or riprap at

station 74 and western edge of riprap at station 113) and the pile of riprap reached a

height of 2.84 feet near its center (station 93). On the western side of this pile of riprap,

there was another scour pool in the wider channel, which reached 2.06 feet in depth

(station 122). This scour pool was 19 feet in width (measured from the edge of the

riprap [station 113] to the right bank of the wider of the San Pedro River’s two channels

at this location [station 132]). Between the wider, dry channel and the narrower, active

channel was a large point bar with cottonwood trees from station 132 to station 191.

The slope from the point bar down to the edge of the left bank of the narrower, active

channel averaged between -16.5 and -21.7 degrees. Station 191 in cross section 1 marks the left bank of the narrower, active channel, which measured 16 feet in width (station 191 at the left bank to station 207 at the right bank). The thalweg of the active channel was measured to be 0.4 feet in depth (station 197.3). The average slope of the right bank from the edge of the active channel to the right bank benchmark ranged between 25 and 40 degrees.

Cross section 2 (XS-2; Figure 18) was located approximately 80 feet downstream

from cross section 1. Benchmarks established for cross section 2 similarly are

cottonwood trees on the left and right banks of the river, each marked with a nail and

orange spray paint. Cross section 2 captures topography downstream of the riprap and

scour pools seen at cross section 1. The average slope from the edge of the left bank

into the main channel at cross section 2 was -9.8 degrees. The slope in the channel

varied between -2.3 and -4.8 degrees from the left bank toward the thalweg. From the

thalweg of the wider channel to the point bar near the right bank, the average slope was

approximately 4 degrees. At the western edge of the wider channel before the point bar,

the bank was incised by 0.58 feet (station 94.5). The slope from the point bar down to

the edge of the left bank of the narrower, active channel averaged between -22.3 and –

65.4 degrees. The thalweg of the active channel was measured to be 0.4 feet in depth

(station 147.64). The average slope of the right bank from the edge of the active

channel to the right bank benchmark ranged between 41.6 and 57 degrees.

Cross section 3 (XS-3; Figure 18) was located the furthest downstream,

approximately 145 feet from cross section 2 (225 feet from cross section 1). Again,

benchmarks established for cross section 3 are cottonwood trees on the left and right

banks, each marked with a nail and orange spray paint. Cross section 3 captures large

debris accumulation at the cottonwood trees at the point bar between the wider dry

channel to the west and the narrower active channel to the east. The left bank of the

wider dry channel had incised by 1.54 feet (station 12). The average slope in the wider

dry channel ranged from -2 to -4 degrees from the left bank toward the right. At the right

bank/west edge of the wider main channel (station 87.5), a pile of LWD approximately

8.5 feet in height and 9 feet in width accumulated upstream of a stand of cottonwoods

near the point bar between the wide dry channel and narrow active channel. The

average slope from the channel to the top of the debris pile was approximately 51.8

degrees. From the top of the debris pile down to the left bank of the active channel, the

average slope was -78.8 degrees. The slope of the left bank leveled off between

degrees and degrees to the thalweg of the active channel. The thalweg of the active

channel was measured to be 0.4 feet in depth (station 120). The right bank of the active

channel was incised by 2.64 feet. The average slope of the incised right bank from the

edge of the active channel to the right bank benchmark ranged between 13.2 and 38.2

degrees.

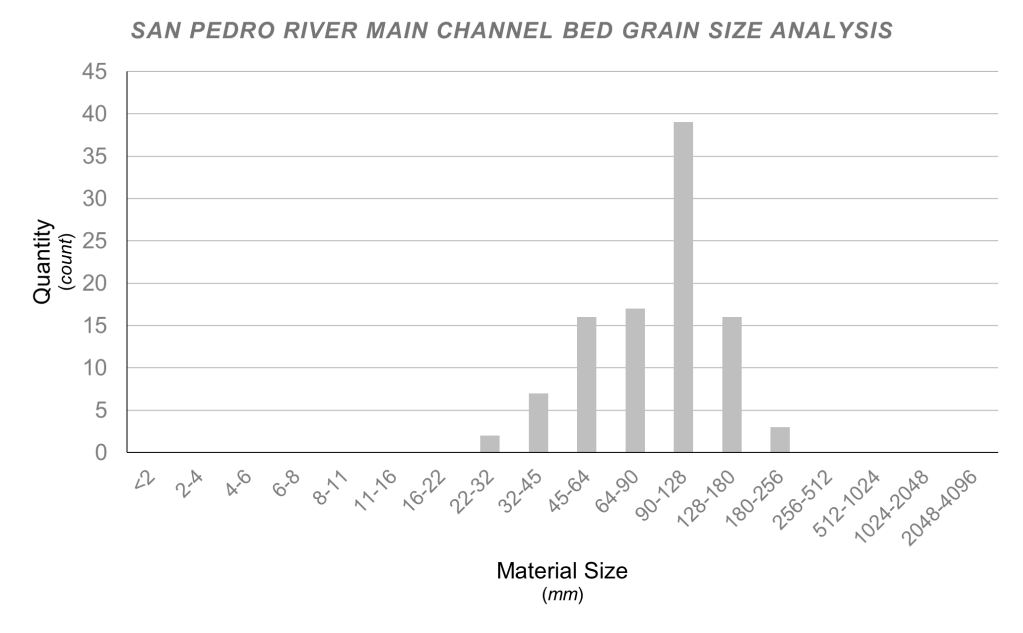

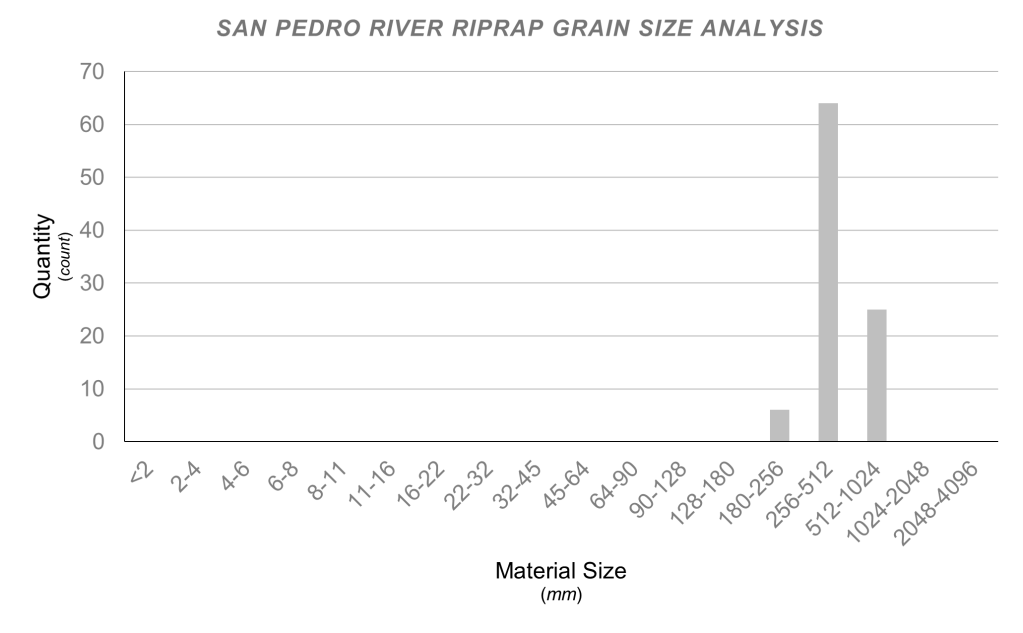

Grain Size Analyses

Grain size distributions from the pebble counts and sieve analysis conducted

during the December 2022 site visit are recorded in Figure 19 and Figure 20. Figure 19

represents the grain size distribution of what was determined to be native riverbed

material, and Figure 20 represents the grain size distribution of the riprap placed by

contractors during construction of the border wall and floodgates.

The mean particle size (D50) was 94 mm (medium cobbles) in the sample of

natural riverbed material and 434 mm (small boulders) in the sample of riprap. The

median particle size was 90 mm in the sample of natural riverbed material and 420 mm

in the sample of riprap. The most commonly occurring particle size was 100 mm in the

sample of natural riverbed material and 300 mm in the sample of riprap. The particle

size at the 90th percentile (D90) was 50 mm in the natural riverbed sample and 612 mm

in the riprap sample. The particle size at the 10th percentile (D10) was 50 mm in the

natural riverbed material and 300 mm in the sample of riprap. The relative standard

deviation in the distribution of the riprap was 0.3, whereas the relative standard

deviation in the distribution of the natural riverbed material was 0.4.

Figure 12 depicts a facies map that highlights the locations where pebble counts

and grain size analyses were conducted. The facies map indicates where riprap was

transported into the large channel downstream of the border wall. At its farthest point

into the channel, riprap was measured to have been transported 54 feet from its original

placement downstream of the bridge. The facies map also notes scour pools, debris accumulation, an incised left bank, and distinct areas composed homogenously of finer-

grained sand in some locations and larger-grained river rock in others. The facies map supports other survey data (e.g., forementioned findings from repeat photo stationing

and cross-sectional surveys) in illustrating the transformation of a flat channel

composed primarily of sand in May 2021 to a more topographically complex channel

with scour pools and piles of riprap in 2022.

Hydraulic Modeling

Results from hydraulic modeling simulations are compiled in Appendix B. Model

results include maximum inundation depth and maximum flow velocity for the following

simulations:

| Simulation No. | Storm Return Interval (years) | Border Condition | Debris Condition |

| 1 | 2 | Free (no wall) | N/A |

| 2 | 2 | Border wall and floodgates | 0′ accumulation (gates clear) |

| 3 | 2 | Border wall and floodgates | 3′ accumulation |

| 4 | 2 | Border wall and floodgates | 6′ accumulation |

| 5 | 50 | Free (no wall) | N/A |

| 6 | 50 | Border wall and floodgates | 0′ accumulation (gates clear) |

| 7 | 50 | Border wall and floodgates | 3′ accumulation |

| 8 | 5- | Border wall and floodgates | 6′ accumulation |

Maximum depth results from Simulation 1 (August 13-15, 2021, event [2-year RI]

with no border wall) illustrate active flow in the river’s main, narrow channel to the east

(e.g., near the right bank), streamflow in the wider (historic) channel, and that the

floodplains have been activated (ref. lightest shade of blue). Maximum velocity results

from Simulation 1 indicate the slowest moving water on the wetted floodplains (ref. dark

blue in map result), with higher velocities at the main narrower channel and the wider

historic channel surrounding it, as shown in green. The highest velocity flows appear to

be downstream of the wall where the river takes a sharp bend right/east, as indicated in

yellow/orange.

Maximum depth results from Simulation 2 (August 13-15, 2021, event with the

border wall and no debris) indicate similar results to those from Simulation 1 with

flooding slightly increased upstream of the wall on the right bank. Similarly, maximum

velocity results from Simulation 2 appear mostly consistent with simulation 1, except

velocity appears to have slightly increased at the floodgates compared to Simulation 1,

as indicated by the strip of green around the border wall.

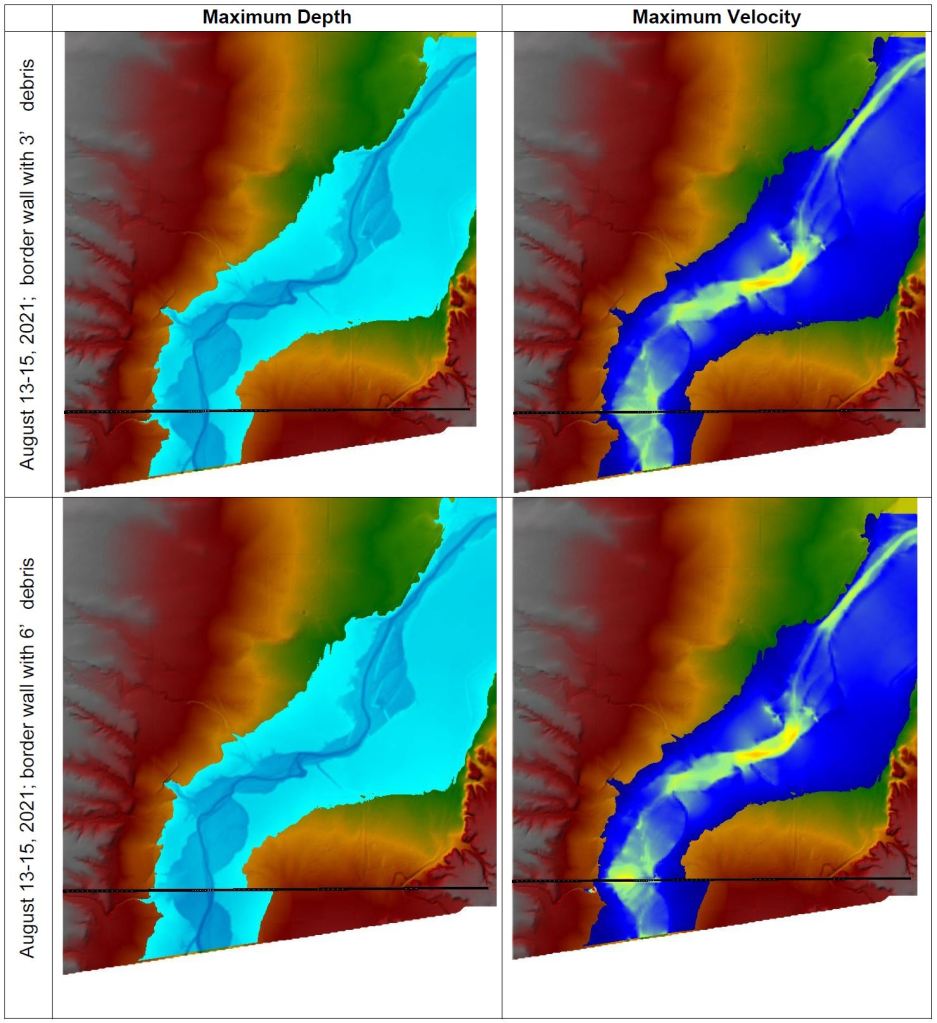

Simulation 3 (August 13-15, 2021, event with the border wall and 3 feet of debris

accumulation) follows the same trend: there is a visible slight increase in flooding

upstream of the border wall on the right bank of the river, as shown in the maximum

depth result. The maximum velocity result from Simulation 3 indicates another slight

increase in velocity at the floodgates relative to Simulations 1 and 2, as indicated in

green.

The maximum depth results from Simulation 4 (August 13-15, 2021, event with

the border wall and 6 feet of debris accumulation) illustrated the most increased flooding

on the upstream, right bank side of the wall relative to the “free” condition (Simulation

1). A slight increase in flooding on the left floodplain (relative to Simulation 1) is also

detectable. Similarly, the maximum velocity results from Simulation 4 show that the flow

velocity around the border wall has increased relative to the “free” condition without a

wall (Simulation 1), as indicated by yellow highlighted around the border wall near the

center of the channel in Simulation 4 results.

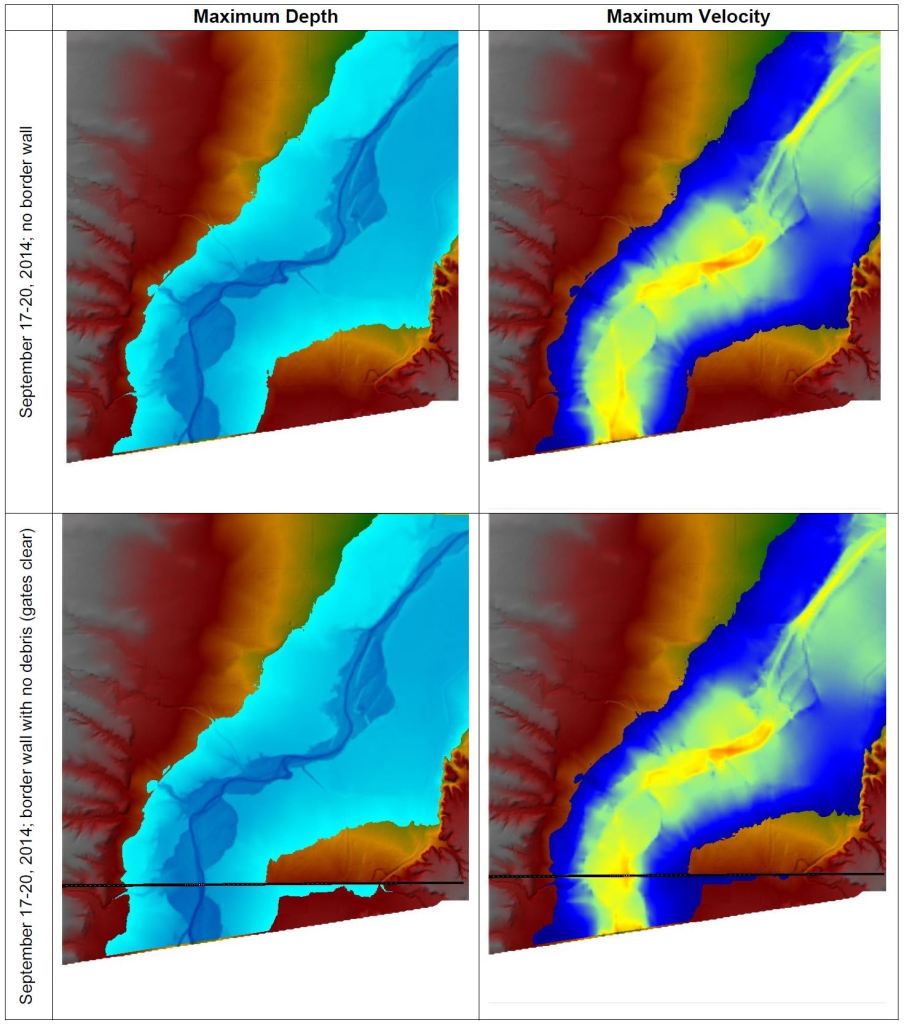

Hydraulic modeling results from simulations with a 50-year flood (Simulations 5-

8) follow a similar pattern as the results from simulations with a 2-year flood

(Simulations 1-4), only the changes are more apparent. Maximum depth results from

Simulation 5 (September 17-20, 2014, event [50-year RI] with no border wall) again

illustrate active flow in the river’s main, narrow channel to the east (e.g., near the right

bank), streamflow in the wider (historic) channel, and that the floodplains have been

activated (ref. lightest shade of blue). The floodwaters extend further east and west onto

the floodplains than in Simulations 1-4 with a 2-year flood event. Maximum velocity

results from Simulation 5 indicate the slowest moving water on the furthest edges of the

wetted floodplains (ref. dark blue in map result), with higher velocities at the main narrower channel (indicated in orange and red) and the wider historic channel

surrounding it, as shown in green. Velocities appear to be higher than in Simulations 1-4

with a 2-year storm event. In Simulation 5, the highest velocity flows appear to be

downstream of the wall where the river takes a sharp bend right/east, as indicated in

orange and yellow. This is consistent with the maximum velocity results from

Simulations 1-4, however, in Simulation 5, the velocities in this area appear higher (as

indicated by more orange compared to yellow in Scenarios 1-4). Additionally, more of

the streamflow is moving at a higher velocity than in Simulations 1-4. Velocities also

appear increased at the upstream edge of the study boundary, as indicated in orange

on the lower edge of the Simulation 5 maximum velocity result map.

Maximum depth results from Simulation 6 (September 17-20, 2014, event with

the border wall and no debris) indicate increased flooding upstream of the wall on the

right bank and extending across the floodplain. Maximum velocity results from

Simulation 6 illustrate increased velocity in the main channel at the floodgates in

comparison to the “free” condition (Simulation 5), as indicated by the line in

yellow/orange across the border wall.

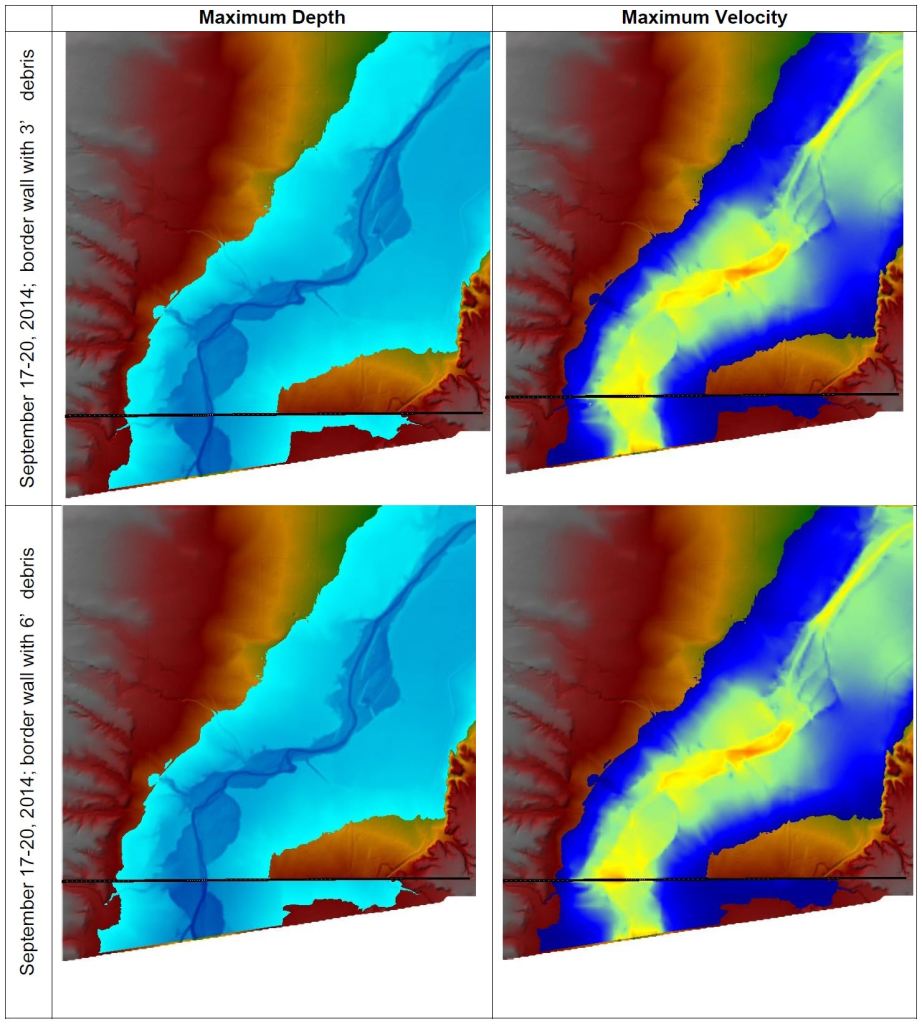

Maximum depth results from Simulation 7 (September 17-20, 2014, event with

the border wall and 3 feet of debris accumulation) indicate increased flooding on the

right bank on the upstream side of the wall more significantly than seen in Simulation 6

results. Flooding on the left bank appears relatively unchanged in comparison to

Simulation 6. Maximum velocity results in Simulation 7 do not appear to have

significantly changed from Simulation 6.

Maximum depth results from Simulation 8 (September 17-20, 2014, event with

the border wall and 6 feet of debris accumulation) depict the most extreme increase in

flooding upstream of the wall relative to the other 7 simulations performed. The

maximum depth results appear to depict slight but insignificant increases to flooding on

the left floodplain upstream of the wall. Maximum velocity results from Simulation 8

again depict increased velocities appearing to concentrate around the border wall’s

floodgates (as indicated in orange), only in this simulation, the increased velocities

appear to have shifted west in the direction of the left bank/smaller floodgates.

Overall, the hydraulic modeling results compiled in Appendix B illustrate

increased flooding (ref. maximum depth results) upstream of the border wall on the right

bank/floodplain in all scenarios where the border wall is present, regardless of if the

gates are clear from debris. Maximum velocity results indicate increased velocity at the

floodgates in the conditions where the wall is present, which may indicate scouring.

Model results show that flooding upstream of the wall is exacerbated in the 50-year storm (September 17-20, 2014, event) with 6 feet of debris accumulation.

Discussion

The key results from photo stationing between May 2021 and December 2022

illustrate that the channel downstream of the border wall had changed from a relatively

flat, sandy riverbed to a topographically variable bed composed of distinct areas of fine

sediments, medium cobbles (river rock), and small boulders (riprap). The incision of the

left bank at the time of the December 2022 survey is visible in multiple photo points (ref.

results from stations 7, 8, and 10), as is the large pile of riprap that had been

transported into the channel (ref. results from stations 7, 8, and 10). The movement of

LWD #101 between May 2021 and December 2022 surveys is also apparent in photo

stations 7 and 8.

The seasonal difference between the two surveys is apparent in comparison

between the photo stationing results. The 2021 survey was conducted in May (the driest

time of the year and before monsoon season), and in contrast, the 2022 survey took

place in December (following monsoon season and with potential for winter

precipitation, as was evident by active streamflow in the narrower channel). It is unclear

to what extent the season of each survey influenced the results. Perhaps following the

December 2022 survey, there may have been additional late winter storms—smaller in

nature than the large monsoon floods—that may have deposited fine sediments in the

channel, changing its bedform to more closely resemble what was observed during the

May 2021 site visit. Ideally, future site visits will be conducted during the same season

on (at least) an annual basis for a more consistent image of the river’s change over time

at the same point each year.

Photo stationing results—which are more qualitative in nature—are supported by

results from the debris surveys, cross-sectional surveys, and grain size analyses.

Debris Surveys

As referenced in photo station results from stations 7 and 8, LWD #101 (tagged

in May 2021) was not recovered during the December 2022 site visit. LWD #105—

which was 18.5 feet in length and 3 feet in width and situated up on the right bank of the

eastern channel—was the only piece of LWD recovered in December 2022. Since only

1 of the 9 pieces of LWD surveyed in 2021 was recovered in the December 2022

survey, it may be that the 2021 and 2022 storms were substantial enough to transport

the 8 pieces of unrecovered material downstream beyond the 0.3-mile study zone. Due

to time constraints, we were not able to travel further in search of the debris. Given

more time and additional team members assisting in search of the debris, we may have

recovered more of the May 2021 LWD. The LWD we recovered in December 2022 was

limited to what 3 people could find in the span of approximately 4 hours. It is also

notable that 1 of the 3 members in our December 2022 survey group had surveyed the

LWD initially in May 2021, meaning that she had the clearest picture/memory of what

each piece of LWD looked like and its position in the channel in May 2021. The other

two members of the survey group were searching for debris based on photos, GPS coordinates, and written description alone, which may have not been sufficient to

recognize the LWD in field. It may also be that how LWD #105 was situated in the bank

(e.g., up higher in the bank, somewhat partially embedded in sediment, and

adjacent/wedged between existing cottonwoods) that held it in place during the 2021

and 2022 storms compared to other LWD that appear to have been transported

downstream. Future surveying following the next seasonal storms will be needed to

further investigate.

Another reason that so much of the LWD was not recovered in December 2022

may be that the floods had broken the debris into smaller pieces, rendering them

unrecognizable. It is notable that the debris tagged in May 2021 was tagged in a central

location on the LWD but was not painted. If the debris was broken even into only 2 or 3

smaller fragments, it would have been essentially impossible to recognize without the

tree tag visible. Considering this possibility when tagging new recruitment LWD during

the December 2022 site visit, we were careful to use orange spray paint along the full

length of the LWD in hopes that—if the debris breaks apart in future floods—remnants

of it will be recognizable in future site visits.

Alternatively, additional debris and sediment may have accumulated and buried

the LWD tagged in May 2021, though this was not evident from field observations

during the December 2022 site visit.

The largest flood between the May 2021 and December 2022 surveys had a

peak flow of 7,410 cfs (August 2022), which is approximately a 4-year return interval

(USGS, 2022). It is notable that a relatively small flood (e.g., one that would be

expected every few years) has resulted in such distinct changes to the channel,

especially the formation of scour pools and the transportation of the riprap—which was

purportedly placed for erosion control—54 feet downstream from where it was observed

in 2021.

Tracks from grading equipment both up and downstream of the border wall were

visible at the time of the December 2022 site visit, which leads us to believe that debris

and sediments had been removed and/or the channel around the wall regraded before

the December 2022 site visit. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has not made

public their costs for maintaining the border wall and/or for repairing damage from the

2021 and 2022 storms (Miroff, 2020). Considering the natural flood and debris transport

regimes of the San Pedro River, it is clear that removing accumulated debris and even

regrading the channel for flood conveyance will be required on a seasonal basis,

making maintenance costs a regular annual bill. Additionally, the San Pedro is only one

example of a transboundary river, as there are many other rivers and creeks (such as

the forementioned Silver Creek) that cross the border and would require similar

seasonal maintenance, thus magnifying yearly costs.

The American Immigration Council reported in 2019 that $274 million was spent

on border fence maintenance in 2017, before the wall was extended over the San Pedro River and other areas (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2017). Continuing the

wall over an additional 400 miles of the southern border in 2020 is estimated to have

tripled these maintenance costs to more than $750 million annually (American

Immigration Council, 2019).

Channel Surveys

Cross section 1 (XS-1) indicates the most varied topography of the three sections

surveyed, as this area was closest to the floodgate structure which may have been

starving the downstream area of sediment due to debris damming, creating a “hungry

water” effect (Kondolf, 1997). This sediment starvation may be what resulted in the 5-

foot incision of the left bank and formed the surrounding scour pools in the wider

channel. Cross section 2 (XS-2) indicates more of a “natural” channel form, presumably

what XS-1 may have looked like prior to construction of the wall, had the area been

surveyed in 2021. It is notable, again, given the timing of the December 2022 survey,

that there may have been additional, smaller winter storms that could have deposited

finer sediments and altered the river’s facies if surveyed during the dry season. Future

survey efforts should be conducted at the same time each year, ideally during the driest

season (May).

The large piles of debris accumulation observed downstream of the wall at cross

section 3 (XS-3) were not observed during the May 2021 site visit, but it is unclear

whether the presence of the border wall had any effect on the quantity of debris

accumulated downstream of the wall. We were surprised to find such large piles of

debris downstream of the border wall, since our prediction was that most of the woody

material was being trapped upstream of the floodgates. It is unclear whether the border

wall is having any effect on debris accumulation downstream of the wall, and future

surveys will be required to investigate this further.

Ecologically, it also remains to be investigated how this transition of a rather flat,

sandy bed into a more complex channel may affect local wildlife. Some animal tracks

were visible in the mud surrounding the scour pools, which held water at the time of the

December 2022 site visit. It is likely that these scour pools offered watering holes for

local wildlife, which may or may not have been available given the river’s apparent

topography from the May 2021 site visit. It could be that sediment deposition and

increased flooding create a backwater effect, potentially increasing wetland habitat. The

river’s bedform will continue to evolve each season. Further geomorphic monitoring—

perhaps paired with additional surveys of target species—are required to investigate

how new geomorphic patterns influenced by the wall affect different habitats.

Grain Size Analyses

While grain size analyses were not completed during the May 2021 site visit,

photo station results from the May 2021 site visit indicate that the channel appeared to

be of a more heterogeneous and finer-grained (e.g., sandier) bed composition. The

grain size analyses from December 2022 indicate a clear distinction between natural riverbed material (Figure 19) and the riprap placed downstream of the wall following its

construction (Figure 20). The average particle size of the material interpreted to be the

river’s natural bed material was a medium cobble (94 mm). The average particle size of

the riprap (small boulders) were significantly and intuitively larger at 434 mm. With a

relative standard deviation of 0.4, the distribution of the natural riverbed material ranged

between coarse gravels and very large cobbles. In comparison, the distribution of the

riprap material was narrower with a relative standard deviation of 0.3 and consisted of

particle sizes between very large cobbles and medium boulders. The USACE’s original

planning documents for the border wall have not been made public, so it remains

unclear how the design grain size and quantity of the riprap was determined for erosion

control measures. Since the riprap has been transported 54 feet downstream with a

peak flow of 7,410 cfs between May 2021 and December 2022 site visits, it remains

unclear for what recurrence interval storm the riprap material was sized.

The channel’s transformation to a more homogenous and variable composition of

bed material may be due to the presence of the wall and increased scouring, moving

the finer bed material downstream and depositing larger particles within the boundary of

the study site. Given the timing of the December site visit, it is also possible that later,

smaller winter storms may have altered the bed composition to potentially return it to a

finer-grained composition. Grain size distributions and bed topography will continue to

evolve with each flood. Additional surveys—ideally conducted at the same, driest time

each year—are required to further investigate how the border wall affects sediment

deposition and bedform.

Hydraulic Modeling

From the hydraulic modeling results, increased flooding on the right floodplain

was visible each simulation with the border wall in place (Simulations 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and

8), regardless of whether debris was accumulated at the floodgates. This flooding may

be because only four of the smaller-sized gates are present on the right bank, so

floodwaters are building up at the wall, which is modeled as an impermeable weir.

Future modeling efforts should build from this model to incorporate variability in

permeability for the floodgates, the wall, and the debris, as this iteration treats each as

an impermeable structure, which is not the reality.

It is notable that flooding is exacerbated in the September 2014 event (a 50-year

RI), especially in Simulation 8 (6 feet of debris accumulation at the border wall).

Presumably, with larger storm events (e.g., a 100-year storm), this flooding would be

extended further onto the floodplain upstream of the wall. This would also mean debris

being carried downstream could be carried onto the floodplain beyond the border wall’s

floodgates, which may require further maintenance. Future modeling efforts should

incorporate sediment transport to further assess where channel erosion or

sedimentation may occur with each storm event and barrier condition. If possible,

modeling should incorporate subsurface dynamics to investigate how such flooding

interacts with groundwater. In the San Pedro River Watershed, any interventions that could have impacts to groundwater are frequently discussed. Further studies could

investigate how large flooding exacerbated by debris damming on the border wall may

act as groundwater recharge. As mentioned previously, investigations into how such

flooding may alter or increase wetland habitat upstream of the wall have yet to be

performed.

Other Observations, Limitations, and Opportunities for Future Study

The scope of this study was unfortunately limited due to lack of data available for

the Sonora portion of the watershed. The digital elevation model (DEM) used in

hydraulic modeling captured only a quarter of a kilometer upstream of the wall, as other

international-spanning DEMs were of coarse (30-meter) resolution. Because the width

of the San Pedro River’s channel at the study site is approximately 200 feet in width, the

30-meter resolution DEM was not sufficient to precisely model the river’s flows on the

site scale defined in this study. The river’s channels were not clearly defined in the 30-

meter DEM, which required me to modify the topography to carve in a representative

channel, introducing a new layer of assumption and uncertainty. This led me to instead

use the USGS 1-meter resolution DEM, which offered more precisely defined

topography at the cost of including more terrain upstream of the border.

Regarding the original hydraulic model used by the USACE to design the border

wall’s floodgates, the original design documents for the border wall and floodgates have

not been made publicly available, and the USACE South Pacific Border District that was

created to manage the construction of the border wall has since been dissolved. It

remains questionable what modeling and assumptions were performed in the design of

the floodgate system for the San Pedro River as well as other rivers that cross the

border.

Lack of connections and access to the Sonora portion of the watershed for

surveying in May 2021 and December 2022 meant that cross sections, grain size

analyses, and photo stationing could only be completed downstream of the wall. To get

a clearer picture of how the border wall and floodgates affect processes of flooding and

erosion on the San Pedro River, incorporating topographical data upstream of the

wall—where the flooding and deposition is occurring—is crucial. Future studies should

prioritize partnerships with organizations and landowners in Sonora, and work with

Customs and Border Protection and the Mexican government to obtain the permits

necessary for surveying work upstream of the wall, including collection of LiDAR. The

Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Watershed Management Group (WMG) lead wet-dry

mapping and beaver survey efforts, respectively, on an annual basis with watershed

stewards (The Nature Conservancy, 2022; Watershed Management Group, 2022).

Ideally, the debris monitoring and surveying methods outlined in this study can be

repeated by local volunteers following seasonal storm events. As evident by the

decades of community-led wet-dry mapping across the length of the San Pedro River,

this watershed has a legacy of community stewardship, action, and cooperation that has

informed regional policy (The Nature Conservancy, 2022). In such a setting, initiating a debris monitoring program seems an appropriate and timely opportunity to engage

community members and catalog how the river’s morphology and debris accumulation

changes over time with the presence of the border wall.

Another limitation of this study is the lack of transparency from CBP regarding

maintenance activities and costs for maintaining the floodgates. During the site visit in

December 2022, we observed tracks from grading equipment beneath the bridge

downstream of the border wall. On the upstream side of the wall, we were able to

observe similar evidence of grading equipment (e.g., tracks and the lack of large woody

debris behind the larger floodgates), suggesting some form of floodgate maintenance

took place following the 2022 monsoon season to move sediments and LWD that would

have accumulated upstream of the wall. It is apparent that some form of seasonal

maintenance, debris removal, and regrading of the channel is ongoing, yet the protocols

and frequency of these operations is unknown. Since both scour pools and evidence of

grading equipment were observed, it is unclear which pools were formed by the river’s

natural process of scouring and which pools were formed by excavating accumulated

sediment and debris. CBP’s full maintenance protocols for the floodgates and border

wall have yet to be shared but are a critical component in understanding to what extent

the river’s morphology is influenced by fluvial processes rather than by maintenance

interventions. Additionally, contracts for the grading and debris removal operations are

not publicly available, and annual costs for maintaining the floodgates are unknown.

Some estimates place annual maintenance costs at a minimum of $864,000 per mile

per year (Hulseman, 2019), and others estimate annual maintenance costs for the

entire length of the border wall up to $750 million (American Immigration Council, 2019;

U.S. Department of Immigration, 2017).

Lastly, the design of the floodgates on the San Pedro River is not unique to this

site. Similar designs were employed where the border wall crosses other transboundary

rivers, such as Silver Creek near the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge. The

same limitations to debris transport and longitudinal connectivity that are presented by

the wall on the San Pedro River presumably affect other international waters as well. While there is a plethora of documentation on the impacts of dams, weirs, and other in-

channel structures on longitudinal connectivity of rivers, the border wall floodgate infrastructure represents a novel type of barrier that warrants future study.

Conclusions

As evident by streamflow records and historical accounts of flooding, the speed

and unpredictability in which storm events develop is common to the San Pedro River.

The river’s flow regime naturally fluctuates: nonexistent flow is interrupted by brief

periods of intense flash flooding capable of eroding banks, carving new channels, and

wiping out human infrastructure in a single storm event. The border wall is the latest

iteration in a history of infrastructural projects that bisect the river, and evidence of

debris accumulation and seasonal maintenance to remove it is already apparent.

The changes to the river’s bedform downstream of the wall, the (apparent)

transport of 8 of 9 of the LWD tagged in 2021, and the visible increase in woody debris

accumulation observed during the December 2022 site visit occurred with a peak

streamflow of 7,410 cfs (a return interval of approximately 4 years). Results

documented here following the 2021 and 2022 floods demonstrated that debris is easily

trapped and the channel downstream of the wall has been visibly changed with a

relatively frequent storm event. We have not documented a large buildup of woody

debris becoming trapped in the floodgates yet, though this will inevitably occur in a

larger flow. Hydraulic modeling results indicate that increased flooding upstream of the

wall is likely to occur with a larger storm, especially if debris is already built-up at the

floodgates.

This study has documented trapping of debris on the border wall’s floodgates,

changes to riverbed grain size, scouring, and incision, each of which present more of an

issue for the border wall itself than for the San Pedro River. The San Pedro River will

recover from these effects downstream as local hydraulics will be modified with each

flood and grain size distributions and bed topography will naturally evolve. Whether or

not this has significant ecological consequences remains to be seen. However,

accumulation of debris on the floodgates threatens the structure of the floodgates

themselves, as does scouring under and/or around the gates.

The San Pedro River has been studied extensively and many efforts have been

made to preserve it, especially over the last few decades. The most pertinent issues

have largely been surrounding threats to groundwater and streamflow permanence.

Now, the river is confronted by a new threat, which is the impact of the border wall as a

blockage to mammal migration, as well as the constriction of wood supply. The border

wall is a new type of barrier to a free-flowing river that warrants future study beyond the

San Pedro, as this river is only one in a series of rivers that cross the US-Mexico border

and face this condition.

Bibliography

The AMBER Project (2023). Website accessed. 23 February 2023.

https://amber.international/european-barrier-atlas/

American Immigration Council (2019). The High Cost and Diminishing Returns of

a Border Wall. 6 September 2019.

https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/the_high

_cost_and_diminishing_returns_of_a_border_wall.pdf

Arizona Geological Survey Staff (2009). Holocene Mapping of the San Pedro

River System: A

Geologic Approach to an Environmental Problem – Water Resource

Management.

Website accessed. 02 February 2023.

https://azgeology.azgs.arizona.edu/archived_issues/azgs.az.gov/arizona_geolog

y/summ

er09/article_sanpedro.html

The Arizona Republican (1896). Big Floods at Benson, Cloudburst in the

Whetstone Range, Damage Done to the Southern Pacific, Buildings Washed

Away and Several Lives Reported Lost. The Arizona Republican: VII, 116. 2

October 1896. Website accessed. 20 February 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84020558/1896-10-02/ed-1/

The Arizona Silver Belt (1890). Communication. The Arizona Silver Belt: 3. 30

August 1890. Website accessed. 20 February 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021913/1890-08-30/ed-1/seq-3/

The Arizona Silver Belt (1893). Territorial Items. The Arizona Silver Belt: XVI, 23.

02 September 1893. Website accessed. 20 February 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84021913/1893-09-02/ed-1/seq-1/

Arizona Weekly Citizen (1891). Arizona Weekly Citizen: 2. 14 March 1891.

Website accessed. 20 February 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1891-03-14/ed-1/seq-2/

Arizona Weekly Citizen (1889). From Tres Alamos. Arizona Weekly Citizen: 3. 27

July 1889. Website accessed. 20 February 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015133/1889-07-27/ed-1/seq-3/

Barnes, H.H., Jr. (1967). Roughness Characteristics of Natural Channels. US

Geological Survey Water-supply paper 1849.

The Bisbee Daily Review (1905). Railroads Knocked Out by Rains. 18 March

- The Bisbee Daily Review. Website accessed. 20 February 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024827/1905-03-18/ed-1/seq-8/

The Bisbee Daily Review (1914). Water Damage on San Pedro River to Farms,

Railroads and Highways is Great – Floods Over Mile Wide. The Bisbee Daily

Review: 17, 173. 24 December 1914. Website accessed. 20 February 2023.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024827/1914-12-24/ed-1/seq-1/

Branco, P., Segurado, P., Santos, J.M., & Ferreira, M.T. (2014). Prioritizing