This project so far has used the lens of Western science to look at the problem of debris transport and the border wall as impediment to longitudinal connectivity on the San Pedro River. I now aim to set aside this lens and to widen our perspective beyond the San Pedro Watershed to examine the paradigm from which the border has manifested physically.

Coming from an engineering background and pursuing a graduate degree in environmental planning, I have been challenged in this project to define a narrow scope focused objectively on the border wall within the context of erosional processes and debris transport on the San Pedro River. While this compartmentalization fits into the framework defined by dominant Western science, it does a great disservice to place-specific meanings and questions of justice, ethics, and democracy that lie within the sociopolitical histories of the site. To extend the project into this realm is to peer upstream at the structures of violence rather than effects and harm that are resultant from the physical manifestation of the border. The border wall as a barrier to flows on the San Pedro River stems from a logic that land is property to be contained.

I want to begin by acknowledging my identity as a white person that is not Indigenous to the San Pedro River valley nor the US-Mexico borderlands region. I grew up 200 miles north in Mesa, Arizona, and now am a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, living and working on other Indigenous lands. UC Berkeley resides in xučyun territory, the ancestral, unceded, stolen lands of the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone people, the successors of the historic and sovereign Verona Band of Alameda County. This land was and continues to be of great importance to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and other familial descendants of the Verona Band, and I continue to benefit from living and working on these lands. Similarly, the site I have studied on the San Pedro River resides in ancestral Indigenous lands belonging to the Tohono O’odham, O’odham Jewed, Akimel O’odham, Western Apache, Hopi, Zuni, and other tribes that have and continue to persist in the face of dominant colonial structures of forced relocation and assimilation.

Throughout this project, I do not attempt to represent or otherwise speak for any tribe(s). I do not attempt to claim that my critique of dominant science at odds with traditional ecological knowledge is novel; rather, my intention is to synthesize the work already being done and to apply an anticolonial lens to the case of the border wall at the San Pedro River to imagine potential futures for the site that re-recognize Land as relation. Borrowing insight from Liboiron’s (2021) research protocols “with an orientation to good L/land relations” (123), I explore how monitoring debris on the San Pedro River can be made ceremony by considering our “obligations for each other while embed[ing] long-term relations of care” (Fox et. al. 2017, pg. 4).

A new timeline of settler and Indigenous histories (Figure 1) hopes to represent different realities—one binary and ruled by a “land as property” regime, and another colored by multidimensional experience and relationship with Land—coexisting “separate but parallel paths heading in the same direction” (Liboiron 2021, pg. 127). As one timeline is monochromatic and strictly linear in structure, the alternative is layered, colorful, and multidimensional. The settler colonial timeline begins at Spanish contact with the Americas and moves through various events, wars, treaties, acts, and policies that created the US-Mexico border as we know it today. This same timeline documents the fortification of the border as it becomes a physical structure due to heightened conflict brought forth by policies such as the Bracero program and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). These fear-based policies, acts, and laws reinforce colonial ideations of “land as property” over time, leading to the rising of the border wall in recent decades. The wall has proven only to continue to become more extensive and foreboding as time goes on.

Parallel to this path, an Indigenous timeline begins with the Tohono O’odham origin story at Baboquivari Peak. This moves into representations of Indigenous lifeways in the San Pedro River valley: subsistence from corn, beans, squash, and saguaro fruit, successful irrigation practices that worked with the region’s natural monsoon cycles, and general persistence of O’odham language and culture. This timeline also documents Indigenous uprising and resistance to the ideals of barriers and bordering, as can be seen through events like the Chiapas Uprising where the Zapatistas were in direct opposition to NAFTA. Over time, these events act as an erosional force that continue to grate against dominant colonial paradigms. The O’odham people (and others) are still here and they actively oppose the wall and its implications for their way of life.

Individually, the two timelines represent different histories of the US-Mexico border: one from the perspective of European-American settlers, and the other representing Tohono O’odham histories of the landscape. When read together, the timeline illustrates the dynamics between colonial ways of defining land and impacts to the people who resided there first. The fortification of the border wall in the first timeline is met by the subsequent resistance and persistence of Indigenous peoples in the second. This layered and unconventional way of expressing time allows us to incorporate more nuance into the way we interpret the history of a landscape. The landscape is not a static result from a series of actions or events that happened at distinct moments in time. Rather, the landscape is in constant flux and shifts from ongoing processes and decisions that continue to ripple outwards, propagating into other decisions and policies that continue to build off of each other and influence the future. In this way, the attention we place on the dominant histories creates a feedback loop that perpetuates colonial narratives and reinforces their logics of containment. By introducing and centering other perspectives and experiences of the Land, we begin to unsettle colonial power structures through drawing.

Further, while the experience of a landscape varies at different points in time, it is experienced differently on an individual basis. The way I have chosen to represent these timelines is limited to my own experiences and understanding of the site, which are largely based on literature review rather than on personal experience in the landscape. A native to this landscape who has lived here for generations will have a vastly different and more intimate view of their home than what I have been able to express. Similarly, the experiences of native creatures—such as migrating birds, bees, jaguar, saguaro, and others—range even more outside of what I am able to comprehend and represent here, but that does not make them any less valid. By considering other experiences of place and attempting to represent these alternatively to dominant narratives depicting the borderlands as a barren and dangerous region, we can begin to shift the attention (and the power) from colonial control to the underrepresented people, animals, and plants that live there. Reading the landscape differently by acknowledging of the histories of harm and focusing on ongoing perseverance is one of the first steps as an ally to support underrepresented communities in regaining agency of their own futures.

Relationship to Land in the San Pedro River Valley

An Indigenous History

Since time immemorial, Indigenous people have been in-tune with the seasonality of nature’s food availability: rather than settling in a defined location, they moved episodically throughout the landscape, adapting from hunting to gathering and harvesting as their environmental conditions shifted (Marchand & George 2013). The Indigenous people of the San Pedro River valley region—the Sobaipuri, Western Apache, Zuni, Hopi, Tohono O’odham, Akimel O’odham, O’odham Jewed, and Hohokam— similarly moved about the Southwest without circumscribed boundaries, coalescing culturally (Ferguson et al. 2004, pg. 2). As illustrated by Ferguson et al. (2004), the San Pedro River valley is very much “a diverse composition of separate but overlapping histories, with many tribes having cultural ties to several of the same places and landscapes… [forming] a mosaic of land, history, and culture” (2). This is important in the context of the San Pedro River and the borderlands because experiences and relationships to place vary from group to group. There is no one tribe, entity, or community that has established “ownership” to the river or its valley. Multiple peoples and individuals may consider sites along the river or outside of it as sacred, and these views were generally respected as tribes naturally shifted around the landscape without claiming any one place (Figure 2). The imposition of the border wall, which cuts across steep terrain, sacred land, and protected areas, has physically eroded the landscape, but has also metaphorically eroded trust and respect for Indigenous lifeways and sovereignty. If these complex overlapping histories were part of the dominant dialogue surrounding the US-Mexico border, it is unlikely that imposing such a wall would have ever been considered.

Spanish contact with what we know today as Mexico was initiated when Francisco Hernández de Córdoba arrived on the Yucatan Coast in 1517. Archaeological records and archival evidence (e.g., Spanish documentation) supports the presence of Sobaipuri and Apache people in the San Pedro River valley at the time of Spanish conquest in the region (Ferguson et al. 2004, pg. 4). The Spanish first made contact with the people of the San Pedro River valley around 1692. They observed the canal networks and early irrigation systems the Sobaipuri people had constructed to tend to thriving fields of beans, corn, squash, and cotton in the villages of Gaybanipitea and Quiburi (Ferguson et al. 2004, 4). The housing they found appeared to be deliberately temporary, only made as shade and shelter from heat and the elements, as the O’odham operated nomadically and traveled to different regions depending on the season for hunting, gathering, and farming (Ferguson et al. 2004, pg. 4). Not recognizing the amorphous way of living in tune with the land, the Spanish “sought to assimilate the Sobaipuri into the colonial system, giving them cattle to herd and encouraging them to build small adobe buildings to lodge itinerant priests” (Ferguson et al. 2004, pg. 4). The Americans that later arrived to the region were attracted to the area because of its positioning as “a buffer between militant Apache groups to the northeast and the Spanish settlements in Sonora” (Ferguson et al. 2004, pg. 4).

As of 2023, the San Pedro River Valley is primarily occupied by non-Native ranchers and farmers, though Apache use has continued (Ferguson et al. 2004, pg. 4). While the Sobaipuri coalesced with the O’odham people after being forced from the San Pedro River valley, the region is still of great importance to them. Ferguson et al. (2004) recount that the “Tohono O’odham gathered acorns, saguaro fruit, and mescal around Babath ta’oag (Frog Mountain), the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson” (6). For the Sobaipuri, the O’odham, and other Indigenous peoples of the region, Land is how their people learn their histories, maintain their traditional practices, and gain their understandings of the world (Ferguson et al. 2004, pg. 6).

Land as Property

A Critique of Colonial Logics

In their excerpt from Two Sides of the Border: Reimagining the Region (2020), Miguel Fernández de Castro and Natalie Mendoza expound that “the dispossession and extermination of the Tohono O’Odham in Mexico has been silent and invisible, despite the fact that all the signs are there to be seen…the violence exercised in this territory escapes both icon and narrative…forced disappearance is the emblematic form taken by this violence precisely because it leaves you with nothing but scattered traces” (343). In the same excerpt, they further illustrate “the seemingly continuous appearance of the desert covering the Mexican North and the US Southwest…[as] the more the Empire expands its horizon by relying on the iconization of nature, the more images in the lands beyond the line erode down to puzzling fragments” (Fernández de Castro and Mendoza 2020, 343).

In Whiteness as Property, Cheryl Harris catalogues property acquisition in the United States through the taking of occupied lands and settling through labor, which was incorporated into common law in this “new world” through Lockean ideals, effectively confirming and ratifying the experience of conquest into possession of land (Harris 1993, pg. 1728). Because only the forms of possession characteristic of white settlement were recognized and legitimated, and because Indigenous forms of possession were communal in nature and “perceived too ambiguous and unclear,” (Harris 1993, pg. 1722) colonialism flattened the meaning of “land” to “property” (Goeman 2015, pg. 72) and cemented it into law. Contrary to dominant colonial definitions of land, Indigenous ways of knowing land are layered and relational; Land is recognized as life and “incarnates the experiences and aspirations of people…as a meaning-making process rather than a claimed object” (Goeman 2015, pg. 73). In this way, Land is much more dynamic and cannot be represented by a static boundary attempting to contain space.

Mapping & Representation

Modern cartography represents land as a series of parcels and block groups, empowering colonial paradigms and those that hold stake in or legal ownership of property. In the US-Mexico border region, this is particularly evident. Harwell (2020) explains that “the maps that dominate our thinking about the United States and Mexico rehearse the same familiar concerns with the mark on the page, delimiting one colored territory from another.” Similarly, mapping as a representational tool holds an immense amount of power as it communicates and spreads understandings of what land is and who it belongs to, thus reinforcing and seemingly justifying colonial control. As Harwell goes on to elaborate, ”…over the last 500 years, maps have enabled kings, colonizers, settlers, governments, armies, and traders to understand, evaluate, visualize, and eventually dominate and domesticate systems and territories of North America with ever-increasing levels of sophistication… the attempt to fortify an arbitrary line in the sand with some concrete and steel seems like little more than nostalgia when all these systems cross borders without even slowing down.” (Harwell 2020).

Challenging dominant cartographic methods requires us to turn away from ingrained logics that are focused on accuracy and resolution and to instead envision a radical way of re-representing Land. In this way, unlearning colonial methods of representing land is the first step toward reparations for Native peoples. As Danika Cooper (2022) elucidates, “mapping the landscape as the ground for a new collective memory can be a way of not only speculating on a future but also of holding the United States accountable by identifying and spatially delineating the literal transfer of land holdings back to Indigenous peoples. In this way, mapping these lands and visualizing the landscape are key components in ensuring that decolonization is not a metaphor but a series of legal, political, social, and cultural actions in which reparations materialize in the landscape” (pg. 119).

Danika Cooper revisits John Wesley Powell’s proposal for arranging aridlands of the American Southwest by their watershed delineations, rather than by arbitrary political boundaries. Cooper suggests that Powell’s proposal “reveals important cues for moving forward that combine ecological conditions with social values” while acknowledging that implementing such a plan requires an approach at “multiple nested scales” and “necessitates a co-production…between top-down planning and bottom-up citizen participation” (Cooper 2020, pg. 172). Cooper argues that this combination of approaches produces a “culture…more in-tune with the realities of aridland ecologies” (pg. 172).

Powell’s proposal is in direct contrast with the US-Mexico border as it exists today (e.g., an arbitrary linear divide that cuts across the landscape regardless of its topography, presence of waterways, or other local significance). Cooper’s argument calling for a multiscale approach that considers both local stewardship and regional context is in direct correlation with (1) what is missing in the design of the wall at the San Pedro River (e.g., a site-specific geomorphic analysis) and (2) what is required to monitor the river at the border wall (e.g., local engagement and advocacy on both sides of the border).

Western Science and Relational Knowledge

The first part of this thesis aimed to develop a repeatable method for monitoring debris at the San Pedro River through the framework of Western science. How can these methods incorporate care and relationality for the San Pedro River as a place and for the others with whom we undertake the process of research with?

Dominant (Western) science and relational ways of knowing, such as traditional ecological knowledge, have long been considered separate. In contrast to relational ways of understanding Land, Western science is largely quantitative and considered “objective.” The myth of objectivity is that it is “a value-based concept that changes over time as Western societal values change” (Liboiron 2021, pg. 124).

More recently, modern engineering practice has moved into the realm of attempting to make use of nature or “work with nature,” trademarking such phrases and continuing to design and exercise power over the land without acknowledging what a deeply colonial practice it is, void of genuine relationship. Science has a place in colonialism, but also anticolonialism, especially if we focus on science as practice, not just content (Longino, Can there be a Feminist Science? pg. 52, cited by Loboiron, 2021, pg. 122). In both thinking about how we define land and how we perform scholarly research (or monitoring) on stolen land, operating with relationality as accountability to each other appeals to our own humanities. Without laboring over the differences, I hope to bring the two frameworks of thinking (dominant science and relational thinking) into dialogue in the context of the San Pedro River as a study site.

As a precedent, Alison Jones and Kuni Jenkins describe that “research in any colonized setting is a struggle between interests, and between ways of knowing and ways of resisting, and we attempt to create a research and writing relationship based on that tension, not on its erasure.” They move toward forms of “empathetic relating which aim at dissolving, softening or erasing the hyphen, seen as a barrier to cross-cultural engagement and collaboration” (Jones and Jenkins, Rethinking Collaboration, pg. 475, as cited by Loboiron, 2021, pg. 33-34). In their CLEAR Lab, Liboiron (2021) considers science as ceremony and “meaning-making,” by stating that “everything you do is a prayer, where prayer shows and reinforces our obligations and gratitude to Land…ceremony is an enactment of our values, guiding principles, and our prayers. Our prayers are the acknowledgment of what is sacred, and what is sacred is how we are connected to everything else” (121). Regardless of identity (Indigenous, non-Indigenous, other), guiding principles and values can be integrated into research methods and protocols to center good Land relations. An example of such work is that of Zoe Todd (Métis), which “attend[s] to the space between and across a) the Euro-Western legal-ethical paradigms that build and maintain the academy-as-fort (or colonial outpost), fixing it within imaginaries of land as property and data as financial/intellectual transaction, and b) Indigenous legal orders and philosophies which enmesh us in living and ongoing relationships to one another, to land, to the more-than-human, and which fundamentally challenge the authority of Euro-Western academies which operate within unceded, unsurrendered and sentient lands and Indigenous territories in North America” (Liboiron, 2021, citing Todd, From Fish Lives to Fish Law, pg. 136). The challenge for us now is navigating how to do our work in the “in-between” space (Liboiron 2021, 113, 136).

Indigenizing Science and Restoration

To make this work actively anticolonial is to make it place-based and untransferable to other contexts, as these methods are at odds with the “universal view of dominant science” (Liboiron 2021, 151). Liboiron (2021) and Fox et al. (2017) describe that from an Indigenous perspective, ‘river’ is not a noun, but both a verb and a being with whom we are in relation to and have obligations toward, and that “all beings have an obligation to the river—and the river to them.” Indigenous and anticolonial science is about “doing science with an orientation to good L/land relations” (Liboiron 2021, 123).

Similarly, Camillus Lopez, a traditional Tohono O’odham scholar, describes having a “deep and abiding sense of kinship” with the Sonoran Desert homelands, and that “in O’odham, it’s a strange thing to own land because the land was there for everybody…it’s there for all, not just people but for all living creatures” (Lopez et al. 2012). Lopez goes on to elaborate that “each place has a place in the natural order…to take something out from the natural order would cause disturbance to the rest of the order…you build something somewhere…you have to remember that there’s an order there… [or] you disturb the balance” (Lopez et al. 2012). Similarly, Gary Paul Nabhan, an agricultural ecologist, ethnobotanist, and writer studying the plants and cultures of the American Southwest, argues that “to restore the land, we have to restory it…this is a missing element of most restoration work…these ritualized parables tell us who we are and how we should relate to the land in a way that underscores the primacy of that relationship” (Nabhan et al. 2012). This is already being done in places like Curridabat, Costa Rica where citizenship has been extended to bees, native plants, and trees to protect biodiversity (Greenfield 2020). Similarly, the Whanganui River in New Zealand was granted legal personhood status and receives the same care, protection, and rights as any citizen (Hutchison 2014).

Challenging Colonial Narratives through Representation

Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Resistance as Erosional Forces

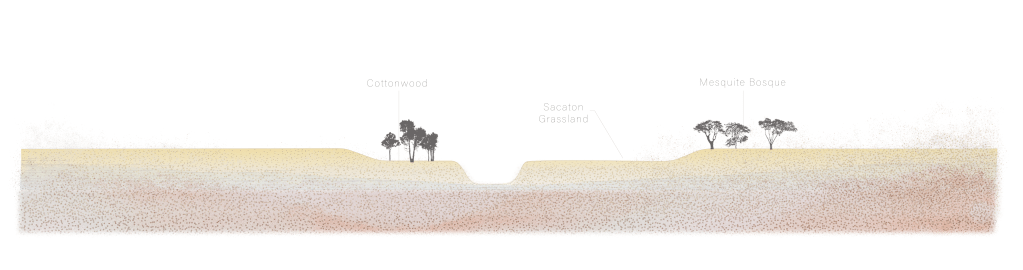

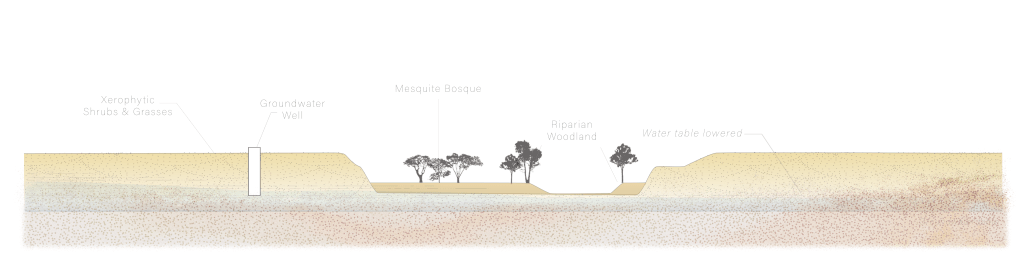

Like stratigraphy revealed in the bank of a river following arroyo cutting, lenses of gravel, sand, and minerals expose the ever-present histories that lay beneath the surface of our immediate knowing, which is limited by the dominant colonial lens. In these serial sections, I attempt to move against the “doctrine of discovery” by approaching interactions with these histories not through excavation, but through a gentle analysis of the pluralities revealed in the bank stratigraphy. These sections describe the process of arroyo cutting by large floods that carved out the San Pedro River’s channels in the late 19th century. In tandem with these powerful floods, settler colonialism has acted as an erosional force to Indigenous sovereignty and multidimensional ways of relating to Land.

Contrasting with the damage narrative presented by describing settler colonialism as an erosional force, Native resistance similarly has acted as an erosional force to these dominating paradigms through persistence and protest. Like the large stands of cottonwoods that arose from the newly deposited sediment beds following the floods of the late 18th century, Indigenous resistance is present and visible in the landscape.

This is complicated by the continued claiming of land and extraction of resources. Specifically, groundwater pumping in the San Pedro River valley threatens the health of the cottonwoods. Just as Native American presence continues, settler colonial ways continue to morph, shift, and challenge Indigenous ways of knowing Land.

Last, the presence of the border wall has led to the accumulation of debris upstream of the wall, but also effectively represents an “emotional residue” (Anzaldua 1987) wherein possibilities for connection and collaboration are undermined by fear and othering. These sections document the process of arroyo cutting and different human-made impositions affecting the river, but they also illustrate the story of settler colonialism’s flattening multidimensional characterizations of Land and ongoing Indigenous resistance in spite of it.

This series of sections has presented another way of using drawing as a tool of landscape architecture to synthesize natural processes and sociopolitical factors, which enables us to represent history differently (here, through stratigraphy). The section drawings depicting arroyo cutting explain the physical processes of erosion and deposition and the resulting change to the river’s channel and surrounding vegetation, which help communicate the importance of large flooding to the establishment of the San Pedro River’s beautiful cottonwoods. Similarly, the section illustrating groundwater extraction communicates how human interventions—when left unchecked—can threaten the health of the treasured canopy by depleting the groundwater table and reducing streamflow. By applying this technique to describe social dynamics between Indigenous sovereignty and settler colonial forces, a familiar process is brought into a new context, offering a new way of understanding the landscape beyond physical processes. These sections integrate physical processes with overlooked social components to shed light on the experiences of Indigenous peoples who have resisted the border for generations. Through this method of drawing, I offer the metaphors of erosion and incision as agents by which colonial forces exercise their power, but also by which Indigenous resistance grates back, encouraging readers to engage with the San Pedro River’s natural history while considering underrepresented histories.

The physical manifestation of the border wall and its floodgates are the result of engineering efforts that treat the environment and the intervention (the wall) like a problem to be solved: the “right” piece being added to a puzzle. Similar to the threshold theory of pollution in which there is a certain degree of harm permissible to enact on the landscape (Liboiron, 2021, pg. 39), the act of designing a border wall-floodgate structure across a river and its floodplain assumes a maximum streamflow of a statistically acceptable return interval (e.g., a 100-year storm), and thus damage from increased flooding, scouring, and erosion is allowable. The engineering is based in probabilities and cost-benefit analyses and treats sociopolitical histories and Indigenous ways of knowing Land as separate and peripheral. While the field of engineering engages with the environment from a distant and narrow scope, there is an opportunity for landscape architecture to synthesize hydrologic, geomorphic, and sociopolitical realities and to engage with them beyond a binary “problem-solving” approach by recognizing multiple potential futures or pluralities.

Reparative Futures

Through representational exercises that center Native American perspectives and resistance against the border wall, I attempt to challenge the dominant colonial narratives that frame the site and the border region more broadly. I suggest a series of potential futures for the site that focus on Indigenous sovereignty and organized deconstruction of the border through strategic protest. In refusing to design the site, I hope to nudge others in the field of landscape design to meaningfully engage with the Native peoples whose Land we all reside on.

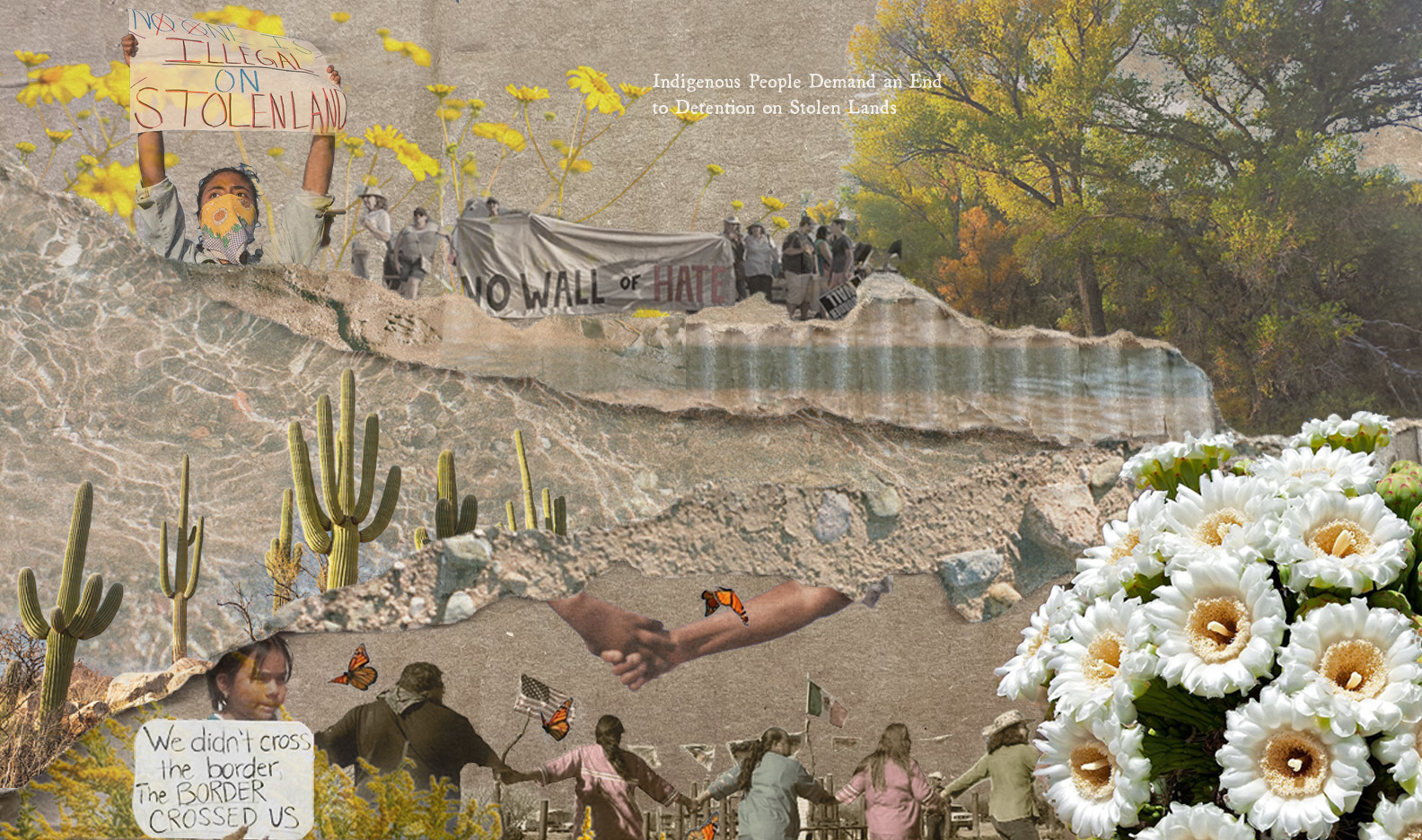

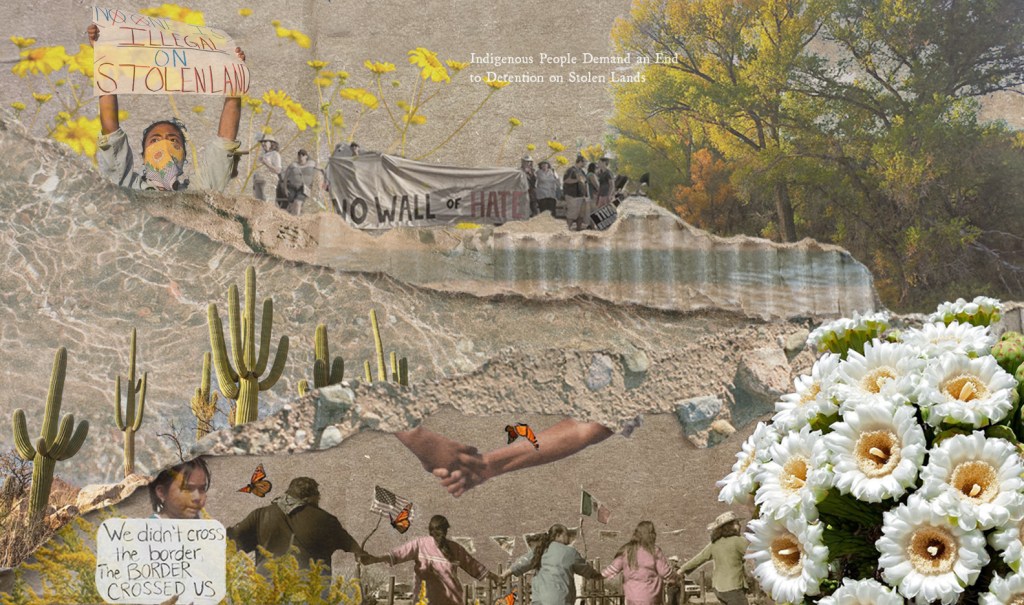

The first collage (Figure 10) is compiled of images of plants native to the southern Arizona, including wildflowers, saguaro, and some of the San Pedro River’s cottonwood canopy. Inlaid with these images are photographs from protests at the border wall. In the upper section of the collage, a woman wearing a bandana holds a sign that reads “no one is illegal on stolen land,” alluding to the case for the border wall as a national security measure with the argument that the land being “protected” from illegal immigrants was forcibly taken from Indigenous peoples who resided there first. Next to this photograph is another photograph taken from a different protest against the border wall, where protesters hold a sign reading “no wall of hate.” In the lower section of the collage, there is a photograph of a small child holding a sign that reads “we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us,” reframing the argument against “illegals” by instead putting blame on colonial systems of property ownership. Lastly, to the right of this photo is another image from a peaceful protest at the border wall where Native peoples have gathered, holding hands and marching in a ring. Mexican and American flags are visible in the background, emphasizing reconnection and community in contrast to othering driven by fear. Splitting the collage are film photos of sediments and the water surface of the San Pedro River taken in December 2022.

Similarly, the second collage (Figure 11) centers on Native people’s perspectives and resistance against the border wall by focusing on Indigenous presence in the landscape and continuation of traditional practices as a form of resistance. In the lower section of the image are older photographs of Native women harvesting saguaro fruits. In the upper left of the collage, a more modern photo of a Native woman prepared to continue this practice is shown. To the right, a Tohono O’odham man is dressed in traditional regalia of vibrant colors. Photos in the upper right depict a woman protesting the “shipping container wall” initiated by Arizona Governor Doug Ducey, and a Kumeyaay woman in peaceful protest of the border wall near Tijuana. Near the center of the collage is a photo of young people who have climbed the wall near Tijuana as a form of protest. The lower section of the collage also includes an image of the ocelot, a mammal native to the Northern Mexico/Southern Arizona region whose movement patterns have presumably been interrupted by the border wall. More film photographs of the site, the floodgates, sediments, and the river divide the two sections of the collage.

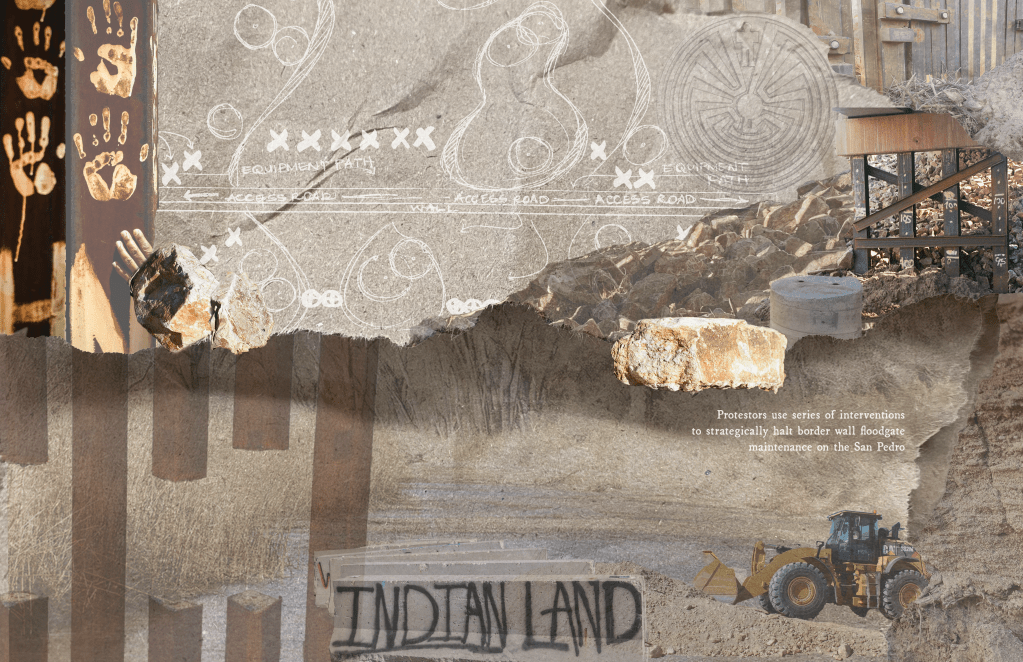

The third collage (Figure 12) includes more photographs from ongoing Indigenous-led protests, including bollards of the wall that have been painted with handprints, inspiring viewers to reconsider humanity in their perspective of the border wall. Below this image is a photo of a severed section of the border wall, suggesting it was cut. Central to the upper part of the collage is a sketch plan that indicates a strategy for an organized “sit in” to interfere with seasonal maintenance of the floodgates. Grading equipment—which is used for removing debris and regrading where sediment has accumulated, as is presumed seasonal maintenance—is shown in the collage as well. A staged sit-in was inspired by the “Starve the Black Snake” project, which suggested Indigenous led interventions to disrupt the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. With the concept applied to the case of the border wall on the San Pedro River, one might imagine people organizing in the river’s floodplain in the way of the grading equipment’s path, interrupting maintenance activities. The collage again is underlaid by photographs of the San Pedro River, sediments, and riprap, where more images from beneath the bridge, including a concrete footing, steel, and a large piece of riprap, are prominent in the upper right. Above these images is a faint symbol of the Tohono O’odham man in the maze, representing the Indigenous people, their origin story, and their continued perseverance.

These collages attempt to grate against the parochial lenses that define land as property, metaphorically eroding these dominant paradigms and re-establishing relationship to Land. In attempting to pivot from colonialist methodologies of landscape design, this project suggests multiple potential reparative futures that may overlap, coincide, or reappear over varying timescales, rather than imposing any particular site interventions. These collages re-center ongoing Indigenous-led protests and imagine a strategic, organized, and Indigenous-led deconstruction of the border. In this way, the project calls for the “re-storying” (Nabhan et al. 2012) of the San Pedro River as a fundamental component of restoring it. Rather than solely analyzing geomorphological patterns and debris transport regimes in restoration, “restorying” implies a shift in mindset that revives relationship to Land, acknowledges histories and structures of harm, and actively attempts to make amends.

Conclusions and Significance

This project has used two parallel systems of thought to study barriers on the San Pedro River where is crosses the US-Mexico border. I have assessed the San Pedro River border wall site in accordance with Western science by providing site survey results that begin to assess how the border wall affects the river’s debris transport regime. Geomorphic and debris monitoring surveys from May 2021 and December 2022 show the formation of scour pools and movement of LWD and small boulders (riprap) downstream of the wall in a 4-year flood. I used hydraulic modeling to predict future scenarios of debris accumulation with varying storm events and predict increased flooding upstream of the border in each case where the wall is present, and most extremely in the case of a 50-year flood with 6 feet of debris accumulation. While ecological effects resulting from changes to the river’s geomorphic and debris transport processes where the wall is present are unknown, the debris accumulation and scouring occurring with the wall in place pose a threat to the integrity of the wall’s floodgates and require regular seasonal maintenance. Debris accumulation upstream of the wall documented by locals in August 2021 was removed by December 2022, supporting that ongoing seasonal maintenance of the border wall at the river is required. While CBP has not made these costs public, estimates of annual maintenance costs for the border wall—including the San Pedro River, other transboundary creeks, and beyond—reach up to $750 million (American Immigration Council, 2019). The border wall as currently constructed interrupts the river’s natural debris transport regime, and the high annual maintenance costs make the wall unsustainable in such a dynamic environment.

Monitoring and survey results from the first segment of this study (Part 1) illustrate debris accumulation at the border wall’s floodgates, which will require seasonal maintenance to keep the floodgates operational and manage flood conveyance. Other key results from Part 1 indicate scouring around the border wall’s gates and vehicular bridge, which may pose an issue to the integrity of the structures themselves. Parallel to monitoring the San Pedro River’s geomorphic and debris transport regimes between May 2021 and December 2022, I have taken a critical stance of mapping and science through exercises in historical representation and imagining multiple futures. Ain Part 2, an investigation into settler colonial and Indigenous histories show that the wall is not appropriate in an environment that has been traditionally traveled without defined borders.

Representational studies in Part 2 synthesize how Indigenous knowledge recognizes the region as one defined by seasonality, movement, and relationship to other plants and animals that inhabit the Land, which contrasts with how colonial nations define land using grids, plots, lines, and borders. Part 2 reframes the border wall as a problem for Indigenous peoples who have been historically harmed, but also refocuses on the experiences of the Tohono O’odham and other tribes in the region. Recognizing these histories of violence and displacement as well as the continued presence of Native peoples in the landscape is the first step toward reparative justice, which is why examining the site outside of traditional Western science frameworks is needed.

Results from Part 1 of this study suggest that the border wall may be a threat to itself under the force of the river’s natural erosional and debris transport processes in this dynamic environment. Part 2 asserts that the border as a whole—and especially as a physical structure—is inappropriate in its context situated on sacred and stolen land. Beyond studying debris transport and geomorphic change narrowly on the San Pedro River, Part 2 acknowledges that the construction of the border wall continues to degrade the land itself, and to challenge and prevent traditional Indigenous lifeways of traversing the land. The design of the border wall does not acknowledge legacies of violence nor engage with the communities that have been harmed. Rather, it is a new iteration of this violence. I have challenged dominant narratives through alternative representations of territories, processes, and histories, and imagine reparative futures that refocus on Native people and their experiences of the site. While these examples are limited to representation, the physical and political work of decolonizing landscape architecture and engineering is still to be done.

Landscape architecture and engineering can be colonial practices when we impose our vision(s) for a site onto the land without considering the variety of native perspectives and relationships to place. Landscape architects and engineers have a responsibility to go beyond land acknowledgments and site signage and instead, actively engage with Tribes, Sovereign Nations, and Indigenous peoples as stakeholders. Where engineering takes a purposefully narrow and neutral scope in site assessment, landscape architects can synthesize layered and interdisciplinary contexts, from environmental and geomorphic analyses to sociopolitical issues that impact underserved communities. Landscape architects carry the potential to help in realizing decolonial futures through developing relationships with Native peoples and elevating their voices to act as agents in their own futures.

References

Anzaldua, G. (1987). The Homeland: Aztlán from Borderlands / La Frontera: the New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Book Company, San Francisco, pp. 3.

Bélanger, P. (2009). Landscape As Infrastructure. Landscape Journal, 28(1), 79–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43324425

Cooper, D. (2023). Spatializing Reparations: Mapping Reparative Futures.

Cooper, D. (2021). Legacies of violence: Citizenship and sovereignty on contested lands. In Landscape Citizenships (1st ed.) (pp. 225-252). Routledge. https://doi-org.libproxy.berkeley.edu/10.4324/9781003037163.

Cooper, D. (2020). Waving the Magic Wand: An Argument for Reorganizing the Aridlands around Watersheds. The Plan Journal 5 (1): 163-184, 2020. doi: 10.15274/tpj.2020.05.01.7

Corner, J. (1997). Ecology and Landscape as Agents of Creativity. Ecological Design and Planning (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997): 81-108.

Ferguson, T.J., Colwell-Chanthaphonh, C. & Anyon, R. (2004). One Valley, Many Histories: Tohono O’odham, Hopi, Zuni, and Western Apache History in the San Pedro Valley. Archaeology Southwest, 18(1), 1-15.

Fernández de Castro, M. & Mendoza, N. (2020). The Stage that Remains. In Two Sides of the Border: Reimagining the Region. Bilbao, Tatiana, Greenberg, Nile, and Ayesha S. Ghosh. Yale School of Architecture / Lars Müller Publishers.

Fine, M. (1994). Working the Hyphens: Reinventing Self and Other in Qualitative Research. In HANDBOOK OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH (pp. 70–82).

Fox, C.A., Reo, N.J., Turner, D.A., Cook, J., Dituri, F., Fessell, B., Jenkins, J., Johnson, A., Rakena, T. M., Riley, C., Turner, A., Williams, J., & Wilson, M. (2017). “The river is us; the river is in our veins”: Re-defining river restoration in three Indigenous communities. Sustainability Science, 12(4), 521–533. https://doi-org.libproxy.berkeley.edu/10.1007/s11625-016-0421-1

Greenfield, P. (2020). ‘Sweet City’: the Costa Rica suburb that gave citizenship to bees, plants and trees. The Guardian, 29 April 2020. Website accessed 04 April 2023.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/apr/29/sweet-city-the-costa-rica-suburb-that-gave-citizenship-to-bees-plants-and-trees-aoe

Goeman, M. (2015). Land as Life: Unsettling the Logics of Containment. In S. N. TEVES, A. SMITH, & M. H. RAHEJA (Eds.), Native Studies Keywords (pp. 71–89). University of Arizona Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183gxzb.9

Harris, C.I. (1993). Whiteness as Property. Harvard Law Review 106(8), 1707-1791. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341787

Harwell, A. (2020). Terra Incognita from Two Sides of the Border: Reimagining the Region. Bilbao, Tatiana, Greenberg, Nile, and Ayesha S. Ghosh. Yale School of Architecture / Lars Müller Publishers.

Hill, K.Z. (2005). Shifting Sites: Everything Is Different Now. In Kahn, A. & Burns C.J. (Eds.). (2020). Site Matters: Strategies for Uncertainty Through Planning and Design (2nd ed.) (pp. 131-156). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429202384

Hutchison, A. (2014). The Whanganui River as a Legal Person. Alternative Law Journal, 39(3), 179–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X1403900309

King, T.L. (2019). The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smm07

Liboiron, M. (2021). Pollution Is Colonialism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1jhvnk1

Marchand, M.E. & George, W. (2014). The river of life: sustainable practices of native Americans and Indigenous peoples. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110275889

McHarg, I. L. (1992). Design with Nature. J. Wiley.

Nabhan, G.P., Loeffler, J., & Loeffler, C. (2012). Restorying the Land. In Thinking Like a Watershed: Voices from the West. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 236-244.

Tuck, E. & Yang, K.W. (2012). Decolonization is not a Metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1-40.

Wiens, J. (2002). Riverine landscapes: taking landscape ecology into the water. Freshwater Biology, 47(4), 501–515. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00887.x